AI is not coming for your job

From the beginning, the current AI boom has been characterized by one sentiment: it’s never been more over. For knowledge workers, there is palpable terror that intelligence too cheap to meter will shortly make every laptop jockey across the world unemployable as a matter of simple economics. Forget third-world sweatshops hollowing out the American manufacturing base, the true threat was always the one that Ned Ludd warned us about: automation making humans obsolete. And unlike the weavers of the 19th century, there will be no ladder of prosperity into the service economy for the human redundancies to climb. This is it, the final obsolescence for any member of the proletariat selling keystrokes for their daily bread.

Total balderdash. Generative LLMs will soon reach a point of undeniably diminishing returns and become just another algorithmic tool that we no longer refer to as “artificial intelligence”, just like we did for chess solvers, speech recognition, image classifiers, etc. A decade from now we’ll refer to these systems by their proper names: code generators, chat bots, automatic writers, speech-to-image. What we won’t call them is intelligent.

The limitations of LLMs

I spent twenty minutes writing a primer on how LLMs work before realizing it’s a distraction from the point I’m arguing and throwing it away. You probably are already familiar with the basics of the tech, and if not there are much better explainers out there than the one I was writing. For now look at this image and be reassured that the author is technically proficient enough to grasp what the tech is and how it works.

Here’s what matters: you train a neural net by showing it a great deal of examples with the answers attached, each of which contributes in some minute way to the statistical weights in the network. That’s how a neural net classifier (which we mostly don’t call AI anymore) works. Generative AI is basically a classifier run in reverse, kind of like Jeopardy! — here’s the answer, now tell me the question. There are lots of details I’m omitting and AI researchers reading this are getting mad, but that’s the basic idea.

What’s more interesting is observing how the technology operates in practice.

Why does it make this dumb error? The LLM, having been exposed to tens of thousands of examples of the gotcha woman-doctor riddle on various web sites, has over-indexed on it. Even when you directly give it the answer to the non-riddle, it can’t help but pattern-match it to the riddle and generate the above nonsense.

Here’s another example of a “classic riddle” with a twist that invalidates it. The LLM (4o again) pattern-matches instead of realizing the riddle cannot be solved with the additional “cabbage can’t be with lion” constraint, and produces obvious nonsense.

But even when the task is to generate a pattern, advanced LLMs screw up when precision matters. Here is Open AI’s o3 model falling on its face when asked to keep track of a number less than 30.

AI boosters say that these are growing pains, and the problems can be solved by shoveling an even larger percentage of GDP at Nvidia. After all, we’ve seen massive performance gains in specific targeted tasks, like multiplying numbers. Just a few months separate these two results:

I don’t want to downplay this result from the Allen Institute, which is genuinely impressive in what it achieves. But it should also be obvious that 99.7% accuracy at a completely determinate task is unacceptable for most domains in which it might be used. Even after explicitly training the model how to perform multidigit multiplication in a grind of iterations, it still gets the wrong answer 3 times in a thousand. Hope you’re not on that flight!

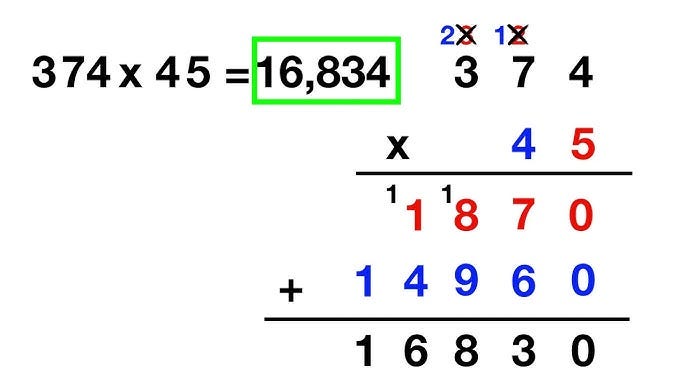

But what’s even more damning is the fact that the model had to be trained on the multiplication algorithm in the first place. You know the one, it looks like this:

A truly intelligent model that has memorized its times table from 0 to 9 (trivial, and it has) and can add any two single digits together (trivial, and it can) and can recite the steps of the algorithm (it can) should be able to apply it to any number of digits, because the algorithm generalizes to any number of digits. But it can’t, not without the specialized iterative reinforcement for the task that the Allen Institute demonstrated above.

The reason this is so, and the reason they are so easily tripped up by fake gotcha riddle questions, is because these models can’t reason. What do I mean by reasoning? Simply: the ability to combine knowledge, analysis, and logic to solve novel problems. LLMs produce a somewhat convincing facsimile of reasoning that breaks down when you poke it the wrong way because it’s fake. It’s pattern matching in reverse. The fact that many problems which appear at first glance to require reasoning can actually be solved by sufficiently complicated stochastic pattern matching is surprising to me personally, but if you’ve ever worked with a not-very-bright programmer who nevertheless got things more-or-less working by copying and pasting stack overflow examples, you start to understand how this can be so.

What about the scaling

I already mentioned the obvious objection to my skepticism earlier: these are just growing pains, and will go away when the digital brains get big enough. Believers point to model performance on various benchmarks, which are improving at an impressive and growing rate.

My counter-objection is even simpler though: these models are already trained on a non-trivial fraction of all information ever created. GPT3 was trained on around 570 GB of plain text, mostly from crawling the internet and digitizing books. Microsoft Copilot consumed every public code repository on GitHub. Sure, there are more words and more code out there that could be fed to the machines. But why would we expect it to make a dramatic difference on top of the literal billions of words and lines of code already used in its training?

Yes, these models are still getting better, and by some metrics they are accelerating. But nobody really knows if this growth has a natural limit or can go on indefinitely. At this phase in the growth cycle, it’s very easy to mistake a logistical curve for an exponential one.

Again: nobody commenting on these topics knows whether the growth in capability we’re observing now has a natural carrying capacity or can go on forever, or where that carrying capacity might be if it exists. Using a naturalist metaphor, we know for certain there is a finite number of prey to be consumed — all the words and all the lines of code ever written, all the artwork scanned and uploaded. True believers assert that some combination of more powerful hardware and more clever algorithmic techniques will overcome the finite amount of data to train on, that sufficiently powerful wolves will grow to the size of the solar system and travel at the speed of light despite having a finite number of sheep to consume. I can’t prove them wrong, but color me skeptical.