Are we at war?

Politics is war by other means, but is it sometimes just war?

Last month’s piece stirred up a lot of sympathetic reactions from fellow travelers and a smaller amount of eye rolling and derision from people on the left denying my lived experience, which I believe they call a microaggression. But there was another set of responses I hadn’t expected, specifically in response to this bit speaking about how I treat peers and colleagues with whom I don’t feel comfortable outing myself.

As for moving to the country to be with “our people”: much to our chagrin, our people are the urban libtards, and we love them dearly. We would not feel at home in a community that voted for Trump as lopsidedly as ours did for Harris.

…

It’s our job to be their friends, their sons and daughters. To love them, as we hope they would love us even if the full extent of our heresy were laid bare.

This was too much for a certain segment of the Very Online Right, who told me as much. “You’re being soft. We’re at war.”

Putting aside the question of whether I should keep my friends who have drifted to the loony side of contemporary politics (I will, thanks very much), I’m quite interested in the second assertion, about us being in a state of war. Are we?

And I don’t mean the metaphorical kind of war, a “war of ideas” or a “battle for the soul of the nation.” I mean an actual war, the kind that is settled primarily with violence or the threat of violence. Are we in one of those, or working up to one? This is a surprisingly hard question to answer, and requires grappling with what civil war looks like in the modern era, and the extent to which the rhetoric of existential conflict spills over into the real world, a continuum that runs from Joy Reid and Stephen Miller, straight through to Tyler James Robinson and Ryan Routh.

Certainly it’s not difficult to find examples of public figures invoking the language of war and revolution, of a struggle between good and evil. All of us can recall news anchors and elected officials solemnly or hysterically warning us that Trump’s election in 2024 would be the last election America ever had. TBD on that one I guess, but does anyone want to bet whether they’ll say the same thing about Vance, or whomever is tapped to succeed him? On the other side of the aisle, there are very many Trump officials willing to describe their disagreements with the American left in the language of war. The remarks Stephen Miller gave at Charlie Kirk’s memorial comprise the best recent example I know of.

Addressing the movement that celebrated or condoned Kirk’s murder:

We built the world that we inhabit now, generation by generation, and we will defend this world.

…

You have nothing. You are nothing. You are wickedness, you are jealousy, you are envy, you are hatred. You are nothing. You can build nothing. You can produce nothing. You can create nothing. We are the ones who build. We are the ones who create. We are the ones who lift up humanity.

To one side, this is a straightforward defense of the West, a condemnation of a social movement that would defame its history and undermine its continuation. To the other, it’s a call for violent extermination. Very charitably, Miller is calling out the radical wing of the Left specifically as being beyond compromise, not the Democrats as a whole. But I can’t begrudge people reading his remarks as addressing the American Left more broadly, as accusing them of being, if not subhuman, then at least less worthy, less part of the project of America.

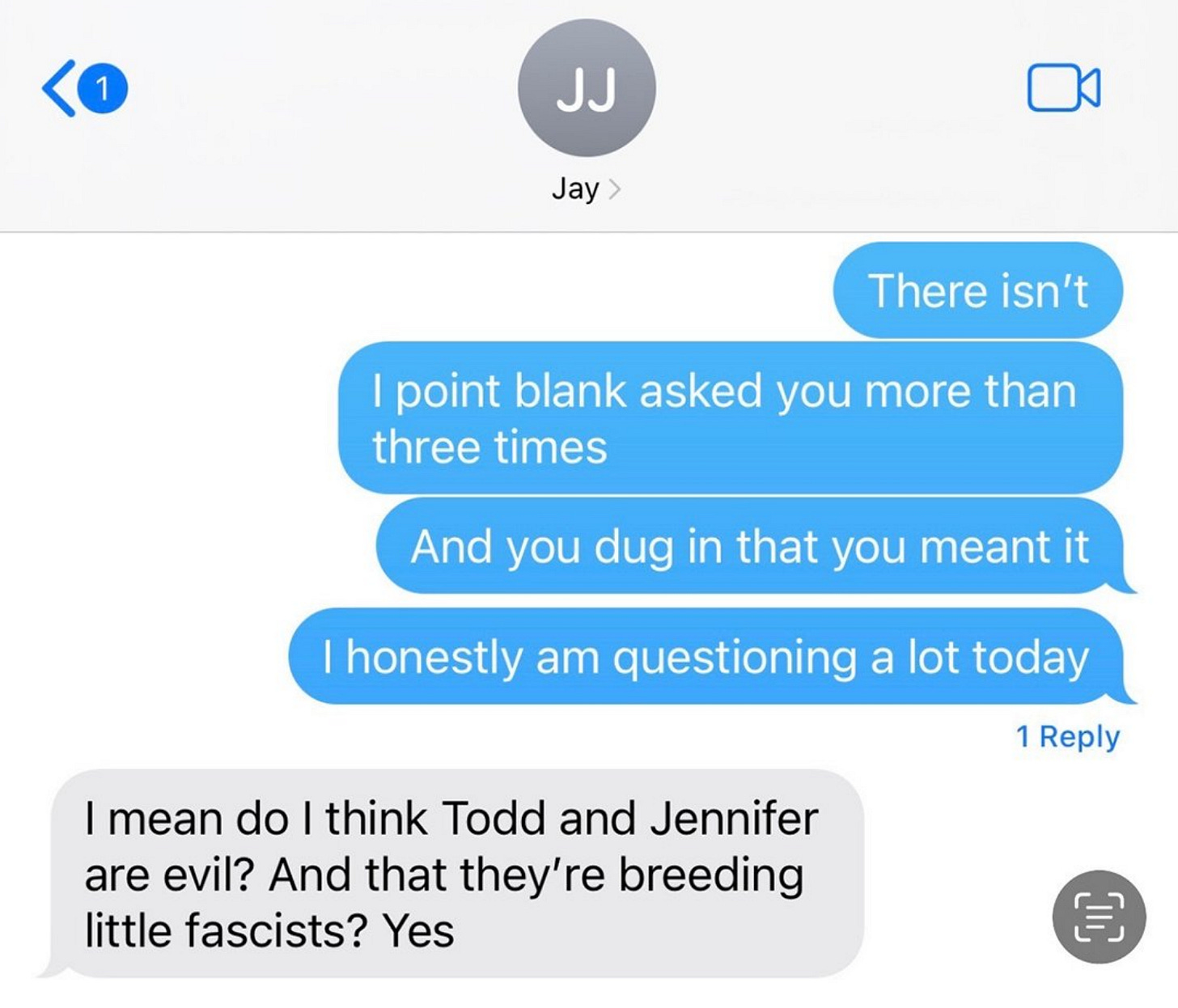

And this isn’t a problem only on the right, or even primarily on the right. You might have seen the recent leak published in the National Review of text messages between Democratic Virginia AG candidate Jay Jones and an acquaintance, wherein Jones fantasizes about murdering his Republican opponent, about his opponent’s wife watching her children die in her arms, and states that they’re evil people “breeding little fascists.” To date, Jones has not withdrawn from the race. The Virginia Democratic Party and the current Democratic candidate for Governor both issued statements supporting his continued candidacy. No major national Democratic figure called for Jones to drop out. In 2025, it’s not disqualifying to be caught wishing death on the opposition, as long as they’re a white Republican man. The alternative is supporting Trump’s fascism.

Everyone understands, at a gut level, that the language of existential conflict, spoken by serious national figures and broadcast widely, is a call to violence that someone, somewhere, will take literally and act on. The official term for this in 2025 is stochastic terrorism, and the danger of such terrorism from the right was breathlessly discussed as a major concern by the left in a series of hand-wringing interviews and media puff pieces right up until the moment that two separate assassins made attempts on Trump’s life. Since then the term has been quietly mothballed, because to take it seriously implicates Joy Reid and MSNBC, to say nothing of many sitting Senators, in our ongoing political violence. If you tell your supporters that democracy and our way of life are at stake, that a literal fascist dictator is coming into power, and you repeat these messages non-stop for the better part of a decade, you cannot then act surprised when somebody takes a shot at Orange Hitler. Your condemnations after the fact of people who took your rhetoric seriously sound mealy-mouthed and insincere. Were you lying then, or are you lying now? If Trump really is an American Hitler, why isn’t taking him out on the table?

Nicholas Decker earned himself a quick rise to internet celebrity and a quick visit from the secret service for asking the quiet part out loud: when must we kill them?

If the present administration chooses this course, then the questions of the day can be settled not with legislation, but with blood and iron. In short, we must decide when we must kill them. None of us wish for war, but if the present administration wishes to destroy the nation I would accept war rather than see it perish. I hope that you would choose the same.

Sensible people on both sides rushed to condemn Decker’s remarks as his article went mega-viral, but nothing he says can be considered remotely controversial. The founding fathers would pound him on the back and buy him a whiskey (assuming they didn’t know he was a gay furry). Electoral politics everywhere are sublimated violence, an alternative to armed conflict that has no teeth unless backed by the threat of the same. No matter how much we might like to protest to the contrary, every person reading this understands their own line in the sand they would meet with violent force if crossed. To rush for the fainting couch at the thought of using force to stop Hitler, to declare oneself above such tactics even if it means the death of six million Jews (to say nothing of the German women raped to death by the Red Army, which we usually do) is either unserious or contemptible. Everyone, everywhere, understands that violence is necessary to redress certain grievances, and we can all point to incidents in history demonstrating the correctness of this view. So what exactly makes our present circumstances different?

It’s impossible to square the apocalyptic, end-of-democracy rhetoric in which we are awash with the claim that violence has no place in resolving these problems. No one believes it. Instead we’re engaged in a sort of never-ending, constantly escalating dual kayfabe in which the threat posed by ideological opponents is existential and unprecedented, but can always be defeated with ordinary electoral politics or by marching with signs. When Trump won his second term, the pundits warning of the fascist threat the night before didn’t urge anyone to arm themselves and prepare to storm the Capital, they urged their fans to write bigger checks. “We’ll get ‘em next time!” I thought you said there wasn’t going to be a next time. Simultaneously, the same pundits and their fans genuinely do believe that violence is necessary or desirable, even while denouncing it and declaring it out of bounds. This is the second layer of kayfabe, the one that papers plausible deniability over the bloodlust of a growing sector of the electorate. It’s indefensible for media figures dealing in the rhetoric of revolution and resistance to feign shock when confronted with escalating political violence, violence they implicitly encouraged for years. You asked for it. You’re getting it. You’re upset? Get real.

And political violence is escalating, not only the recent high-profile assassinations and attempts, but targeted violence against federal law enforcement officers and attacks on federal facilities. A critical mass of radicals have decided the time for violent resistance is right now.

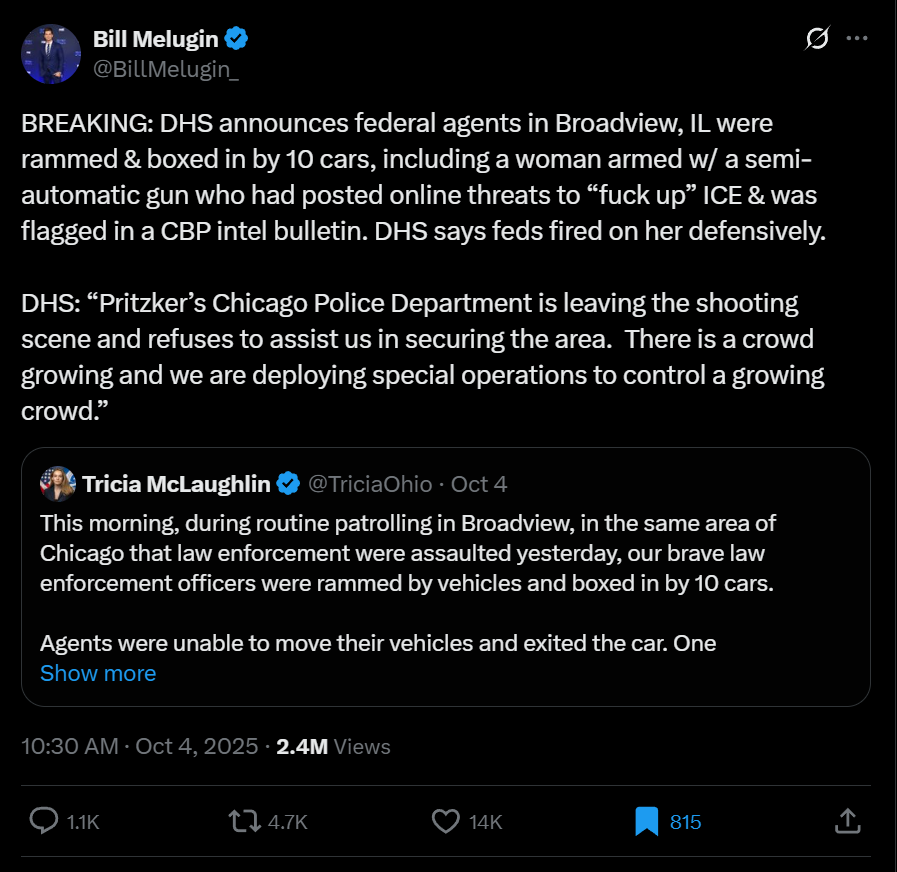

In July, a group of 10 people in Texas staged an ambush outside an ICE detention center, where they phoned in an emergency call, then opened fire from hiding when officers emerged. Last month another sniper in Texas fired indiscriminately into an ICE office in Dallas, including into a panel van that contained illegal immigrant detainees. And in Chicago and other cities, ICE is encountering violent resistance while carrying out deportation operations.

Update 12/3/2025: the above narrative by DHS was disproven when federal prosecutors dropped the case against the defendant fired upon by CBP agents. While there was organized resistance to ICE operations in Chicago, DHS’s claim to have been attacked and to have fired defensively on a protester was not borne out by the evidence.

This is both more and less worrisome than the fiery but mostly peaceful protests of the summer of 2020. It’s far less widespread, but is directly targeting law enforcement officials instead of random acts of property damage and street fights. The last time we saw this level of direct violent confrontation with the government was the radical underground movements of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, a mostly memory-holed chapter of American history chronicled by Bryan Burrough’s Days of Rage. If you don’t want to read the book itself, I recommend the long and detailed review linked in the previous sentence.

“People have completely forgotten that in 1972 we had over nineteen hundred domestic bombings in the United States.” — Max Noel, FBI (ret.)

Days of Rage is important, because this stuff is forgotten and it shouldn’t be. The 1970s underground wasn’t small. It was hundreds of people becoming urban guerrillas. Bombing buildings: the Pentagon, the Capitol, courthouses, restaurants, corporations. Robbing banks. Assassinating police. People really thought that revolution was imminent, and thought violence would bring it about.

One thing that Burrough returns to in Days of Rage, over and over and over, is how forgotten so much of this stuff is. Puerto Rican separatists bombed NYC like 300 times, killed people, shot up Congress, tried to kill POTUS (Truman). Nobody remembers it.

Also, people don’t want to remember how much leftist violence was actively supported by mainstream leftist infrastructure. I’ll say this much for righty terrorist Eric Rudolph: the sonofabitch was caught dumpster-diving in a rare break from hiding in the woods. During his fugitive days, Weatherman’s Bill Ayers was on a nice houseboat paid for by radical lawyers.

…

In 1975, [New World Liberation Front] bombs went off in San Francisco once a week for nine months. They targeted local politicians, including Dianne Feinstein’s house. NWLF bombed a trial, country clubs, the opera. The bombings didn’t wholly stop until 1978. The reason NWLF bombings stopped: the guy who did most of them went insane and killed his girlfriend with an axe.

Comparing today’s skirmishes to the insanity of the 1970s make them seem positively tame by comparison and reminds us how much farther things can devolve and still not be widely recognized as a state of war. And one of the big reasons that we don’t remember this period of revolutionary violence is that institutions on the left sympathized with and made excuses for the terror cells, even rewarding the guerillas with plum sinecures in many cases. Angela Davis participated in an armed courtroom invasion that killed a judge, but was acquitted and then later was granted teaching jobs and honorary doctorates at various prestigious universities. Weather Underground leader Bill Ayers spent years as a fugitive from his role in deadly bombings before having his charges dismissed on a technicality, then rejoined the Chicago community organizing scene that groomed Barack Obama for the national stage.