Compassion for the homeless demands coercion

We have a duty to get people off the street whether they want to or not

American cities are now well into their second decade of an acute homelessness crisis. If you live in a major American city, especially on the West Coast, you’ve seen it first-hand. You’ve edged warily past tents crowding sidewalks. You’ve dodged people passed out in sleeping bags or in bus shelters, lying down or sitting or standing up. You’ve been shouted at by a lunatic, or been on a bus or subway compartment that gets studiously silent pretending not to notice aggressive unhinged behavior, praying it won’t spill over into actual violence. You probably avoid going to certain parts of town, especially if you are a woman or have a family. And even if you don’t, you have noticed the broken plate glass windows and increased security measures in stores that invariably accompany the presence of large numbers of the homeless. The crisis has affected every urban American, stalled urban renewal, and fueled suburban retreat.

But the crisis is not equally distributed, with some cities doing much worse than others. The chart below contains both absolute numbers and per-capita rates. On a per-capita basis, Los Angeles has a homelessness rate 9 times that of Houston.

And note that while NYC has a sky-high homelessness rate, it manages to stick 95% of them in shelters, as does Boston and DC. Meanwhile, 75% of LA’s 55,000-strong army of homeless bivouac down right on the sidewalk, along with two-thirds of the Bay area and half of the Seattle metro. On the West Coast, we prefer our homeless al fresco.

Why? Why does the West Coast in particular do such a poor job of getting the homeless into temporary shelters? Why do West Coast homeless camp on the streets? Very simply — it’s because we have decided to allow them to do so.

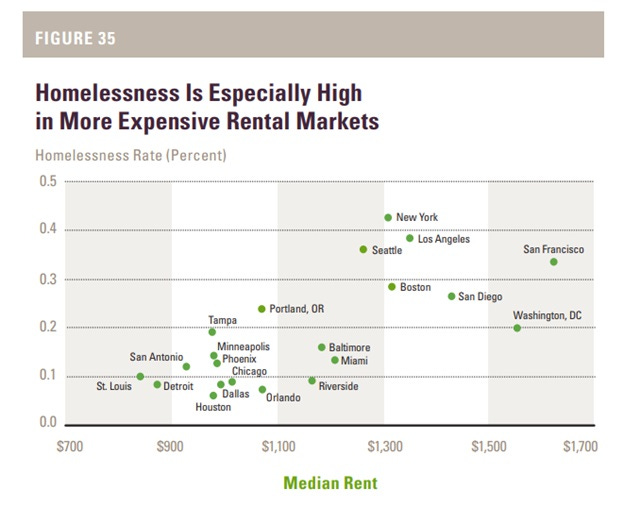

The progressive orthodoxy on this topic insists that homelessness is a simple function of housing prices. Noah Smith published this long piece a couple years ago arguing this at length. His guest author, Aaron Carr, goes down the list of other common rationales for the mass presence of people living on the street, especially mental health and drugs, and demonstrates the correlation of homelessness with these other explanations is quite weak. On the other hand, housing costs seem to bear a strong relationship to the rate of homelessness.

The causal explanation of why high housing costs leads to homelessness goes something like this: a certain percentage of the population is economically precarious, barely able to afford rent, and then a sudden job loss or rent increase, or any other crisis, leads to an eviction which forces them onto the street. It’s a believable and sympathetic narrative, but one must square it with other analyses which find a very modest relationship between changes in the cost of living and changes in homelessness. In the chart below, if you exclude the small handful of cities that saw rent increase by more than 60%, you would be pretty hard-pressed to draw any regression line at all. It just looks like noise.

Personally I approach these statistics with a three-finger pinch of salt, because I suspect what they’re measuring does not capture the problem people complain about when we complain about “the homeless.” It is not the mere fact of homelessness that causes the deplorable street conditions in American cities. Rather, it is the behavior of a small minority of homeless in spoiling the public commons with crime, pollution, open drug use, and aggression. The vast majority of people experiencing homelessness do so on a very temporary basis, with over 75% finding new permanent housing in the first six months.

When activists like Aaron Carr provide figures blaming “the problem of homelessness” on the cost of housing, they’re performing a neat sleight of hand, conflating the experience of temporarily having nowhere to live (literally, homelessness) with chronic street dysfunction among a small permanent underclass (“the homeless”). People involved in the former far, far outnumber the latter but nobody complains about them because they don’t make trouble for anyone. The problem of “homelessness” (temporarily not having anywhere to live) is solved inside of six months for 75% of the people who experience it, while “the homeless” (the permanent street-dwelling underclass) remains an intractable issue immune to billions in spending on a growing cottage industry of faux solution peddlers and paper pushers.

And in any case, none of these graphs or any other quantitative analysis can answer the simple policy question: why does New York not permit its homeless to camp on the streets, but Los Angeles does?

One point on which I agree with Carr and others: it’s not progressivism per se. Yes, progressive judges and prosecutors decline to prosecute the dozens of petty crimes that would remove many of the permanent underclass from the street at least temporarily. But the motivating ideology which permits the voters of San Francisco and Los Angeles to allow street camping in such vast numbers isn’t progressivism, but rather a nihilistic, judgement-free libertinism that refuses to assert that the decision to shit on the sidewalk and smoke crushed fentanyl pills at school bus stops is any less valid a lifestyle choice than living in a townhouse and writing B2B software. It’s the animating spirit of West Coast culture since the days of first settlement, and its flag is well known.