Flag fatigue

Today is the last day of June, which means that starting tomorrow, the rainbow flags flown at government buildings and private residences, hung in coffee shops and hardware stores and dentists’ offices, arranged in colorful collages made of construction paper in public elementary classrooms, splashed onto corporate logo backgrounds on social media and in marketing email headers — in all of the many places that this symbol has occupied pride of place for the last month or so it can start being quietly removed without too much real pushback. Our month-long national rainbow fever is over for another year. But for many of us, those living in deep-blue metros, the arrival of July marks a very minor retreat of the rainbow tide, a return to an only slightly less colorful status quo. The frenzied zeal accompanying their display will dial back a few notches, but the lion’s share of the flags and stickers and children’s books will remain proudly on display year-round, as we have come to accept as the new normal in the last decade or so.

In light of this new normal and in commemoration of its last official day, it’s worth pausing and asking how we got here. When did it become essential that my neighborhood pet store fly a flag celebrating sexual minorities? Am I to understand that gay or transgender individuals are implicitly not welcome to buy dog food at a store lacking such symbolry? It’s close to ubiquitous in many parts of my city (namely the places the nice white progressives cluster), as common to see on a shop door as the opening hours. As an urgent symbol of protest or reassurance it’s flatly contradictory, flying as it does in neighborhoods where the question of gay acceptance is as close to settled as any social issue ever can be. In practice the flag is as incongruous and anachronistic as a sign proudly proclaiming “We do not discriminate by race: Negros and Chinamen welcome to shop here.” Further, its quotidian nature, its sheer humdrum commonness, robs it of any ability to communicate any vital difference in the establishments that display it. It has all the explanatory power of a lighted no-smoking placard on an airplane in 2025. So why must my dentist’s office be, in some small but public measure, queer?

One piece of the puzzle can be found in the writings of Václav Havel, a dissident in communist Czechoslovakia. In his famous essay The Power of the Powerless, Havel attempts to explain the motivations of shopkeepers in displaying state-provided propaganda slogans. This passage has become something of a parable about modern political signaling, usually known by the shorthand title “Havel’s greengrocer.”

The manager of a fruit-and-vegetable shop places in his window, among the onions and carrots, the slogan: "Workers of the world, unite!" Why does he do it? What is he trying to communicate to the world? Is he genuinely enthusiastic about the idea of unity among the workers of the world? Is his enthusiasm so great that he feels an irrepressible impulse to acquaint the public with his ideals? Has he really given more than a moment's thought to how such a unification might occur and what it would mean?

I think it can safely be assumed that the overwhelming majority of shopkeepers never think about the slogans they put in their windows, nor do they use them to express their real opinions. That poster was delivered to our greengrocer from the enterprise headquarters along with the onions and carrots. He put them all into the window simply because it has been done that way for years, because everyone does it, and because that is the way it has to be. If he were to refuse, there could be trouble. He could be reproached for not having the proper decoration in his window; someone might even accuse him of disloyalty. He does it because these things must be done if one is to get along in life. It is one of the thousands of details that guarantee him a relatively tranquil life "in harmony with society," as they say.

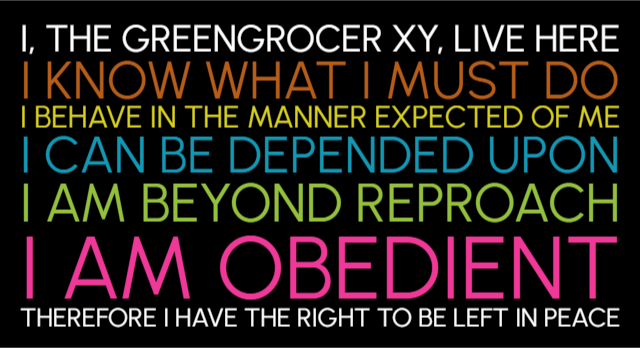

Obviously the greengrocer is indifferent to the semantic content of the slogan on exhibit; he does not put the slogan in his window from any personal desire to acquaint the public with the ideal it expresses. This, of course, does not mean that his action has no motive or significance at all, or that the slogan communicates nothing to anyone. The slogan is really a sign, and as such it contains a subliminal but very definite message. Verbally, it might be expressed this way: "I, the greengrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace." This message, of course, has an addressee: it is directed above, to the greengrocer's superior, and at the same time it is a shield that protects the greengrocer from potential informers. The slogan's real meaning, therefore, is rooted firmly in the greengrocer's existence. It reflects his vital interests. But what are those vital interests?

50 years later in a strikingly different political environment, this passage still holds revelatory power for those newly exposed to it. Like the greengrocer himself, we are awash in symbols and affirmations whose true meaning we usually fail to contemplate. They are so many, they are the water in which we swim. Neglecting to notice and attend to them is the most human of all failings. And none of these proclamations are more strikingly commonplace than the pride flag.

To fly the pride flag is to signal endorsement of an entire pre-packaged value system, one’s allegiance to the American civic religion writ large.

But while there is surely a top-down quasi-coercive element to the display of the pride flag, this explanation remains unsatisfying. Yes, there are agents analogous to the communist party distributing the materials to be put on display, usually in the form of activist groups going door to door and asking proprietors if they would like to show their support for the cause with a donated banner or placard. And yes, the state in its direct legislative capacity does order the display of the same — the featured image of this essay is from a newspaper article about the Los Angeles city council voting to fly the progressive pride flag on government buildings, a very explicit endorsement of what symbols might place one on the friendly side of state power. But there remains a legitimate groundswell element to the movement, organized bottom-up by a dedicated cadre of true believers, widely dispersed through society and in many cases employed by the businesses in question, that needs no nudges from the state or any formal activist organization. Your barista may well have purchased the flag behind the counter and taken it on they/themselves to display, likely as not without bothering to ask the permission of management. Why would they bother? Who could possibly object?