It’s time to build

Housing, and prisons

Publication note 12/3/2025: This essay was my entry into the Boyd Institute’s housing policy essay contest, where it won an honorarium.

Just ask any right-wing masculinity expert on Twitter and they will be happy to prove to you that America doesn’t have a housing shortage. They’ll show you dozens of affordable real-estate listings in flyover country that today’s young people are too lazy and entitled to live in. These spoiled college graduates have the gall to look you in the eye and complain they can’t find a house they can afford when falling-down 2-bedroom ramblers in dying factory towns are going for under $200k. And some of these starter homes are less than a 45-minute drive from a meat packing plant or fertilizer distributor, where a general manager can earn in excess of $65,000 per year.

To left-wing accounts there is an acute housing crisis affecting everyone making the objectively correct choice to crowd into one of the dozen desirable metros every other college graduate of working age wants to live in. But not to worry, there are still great deals to be found, so long as you aren’t racist. You aren’t racist, right? Simply choose from among a generous handful of beautifully diverse neighborhoods where housing is almost suspiciously affordable, many of them a short walk to a bus line or train station. Complaints about the safety and orderliness of these neighborhoods and the public transportation serving them are either overblown, white nationalist propaganda, or both.

Both of these accounts get things right in their arrogance, and both are determined to ignore important economic and social realities that confront a new generation of Americans seeking to enter the housing market.

America doesn’t have a housing shortage. But it does have a shortage of desirable housing, in good neighborhoods, close to good jobs. Efforts to spread concentrated demand for desirable metros more broadly, by changing the preferences of home seekers, are doomed to failure. Our current trend of urbanization is hundreds of years old, driven more by changes in technology than by changes in culture. Treating the problem as one of mere personal preference ignores how long in the making the agglomeration of technocapital has been. You will not convince any critical mass of young people to forego the perks of urban living — proximity to other ambitious young people, cultural amenities, and of course access to professional jobs. Nor will you convince anyone outside of a dedicated cadre of true believers to discount the evidence of their own eyes and move to an urban neighborhood where rent is depressed by crime and disorder, where public transit is haunted by the same. Not if they can afford another option. Not if they can afford a car and a commute from a more orderly place.

Nor can you lure young professionals from their urban and suburban enclaves by artificially bolstering the economic prospects of flyover territory. The well-meaning idea to re-locate federal department offices to slowly dying former factory towns may save those particular towns for a time, but will not create new desirable metros, only new second-tier towns one small step above the ones young people are dying to escape. And with the possible exception of Starbase, company towns are a dead letter, for the same reason: a person uprooting their entire life to relocate for a job prospect will, all else being equal, choose a destination with other options if this one doesn’t pan out. You can get incredibly mission-driven people, like those who dream of colonizing the solar system, to move to your special economic zone. And people with few other prospects, like our massive federal bureaucracy, will suffer as they must to remain employed. But normal, middle-of-the-road college educated professionals will keep choosing New York and San Francisco, and they’re right to. That’s where their peers are, and that’s where the jobs are.

Where does that leave us? If a few dozen desirable metros continue to capture most of the new job prospects and therefore new residents, why won’t their housing prices continue to inflate ever higher? This is the path most major metros are currently on, and they all have two things in common: they refuse to build enough new housing, and they refuse to adequately police their bad neighborhoods. Both of these are policy decisions, and the federal government must break them of both, at the same time, with the same legislation.

For decades, housing policy at every level of government has served to subsidize demand: housing vouchers; sweetheart loans to certain privileged classes; new homebuyer credits; the mortgage interest deduction. All of these policies send more dollars chasing the same scarce supply of housing, driving up prices in the metros where population growth clusters. All of them are counterproductive to making housing affordable. It’s time for a new approach. It’s time to subsidize supply.

It’s time to build, and it’s time for the federal government to help.

As we’ll see in a moment, the money to accomplish a significant increase in multi-family home production is not astronomical by the standards of the federal government, but for it to be deployed, cities and states must get out of the way. Which means we must first address the reasons why so many of our most desirable cities so consistently oppose every effort to increase density.

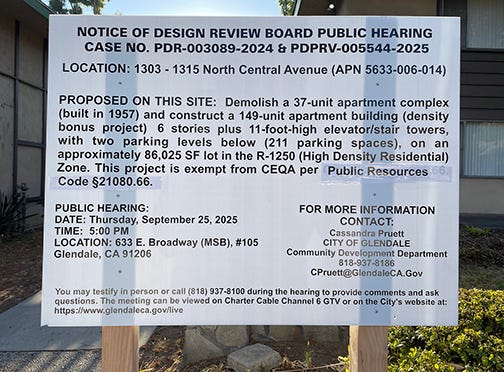

Cities have a whole slew of procedural mechanisms by which new construction is slowed down and made more expensive. Historic preservation ordinances in San Francisco and other anti-density cities prevent derelict shacks being torn down and replaced with apartments. Many cities require a lengthy period of public notice, comments, and hearings before construction can begin, procedures which frequently drag on for years. Some municipalities require developers to include a certain number of low-income units, which naturally lowers the income they can expect to reap from the finished building and drives up the rent on every other unit. Once a project is finally approved, cities inflict a radically cumbersome and expensive permitting and inspection process that introduces further delays and inflates the final cost. And last but not least, we can’t avoid mentioning the final boss of urban density arguments: restrictive zoning. Cities dedicate broad swathes of their footprints to low-density development, either topping out at two or three stories, or restricting entire neighborhoods to single-family homes only.

All of these mechanisms to stymie density can best be thought of as rationales, ad-hoc excuses motivated by other concerns entirely. Neighborhood residents will use every tool at their disposal to prevent density because they accurately perceive that it brings crime and disorder along with it. Dismissing these concerns as racist or classist, sneering at the people expressing them as parochial NIMBY rubes standing in the way of progress, won’t put such concerns to rest. It doesn’t help the clarity of the debate that the urban liberals who live in neighborhoods opposing density are ashamed of the real reasons for their opposition, talking about “neighborhood character” or other canards to avoid admitting the ugly truth that they fear their prospective new high-rise neighbors, especially the ones in the mandated affordable units. And they’re right to.

Americans can only isolate themselves from crime and disorder through price discrimination, and this ugly truth is at the heart of all American housing policy. As long as Americans correctly intuit the relationship between density and crime, they will oppose the former to avoid the latter. And because we live in a free, democratic society, they will successfully find ways to do so through policy. This is why we find ourselves in the position that we do vis a vis density, and why it’s so difficult to make forward progress.

Any credible solution to housing affordability must begin by addressing the elephant in the room and crushing urban crime and disorder. Without the guarantee that new density won’t compromise the peace and safety of their neighborhood, Americans will oppose it, and even if they ultimately lose the battle, the procedural hurdles they introduce will inflate costs and slow construction to well under the pace needed to accommodate growth, let alone drive down rents. A generation hence the NIMBYs may ultimately have lost the battle against density, but young Americans paying crippling rents can’t afford to wait that long. We cannot defeat the NIMBYs in our lifetime and remain a democratic society — if we are to silence their objections to density by force of law, we must also truly address their concerns, by drastically reducing urban crime and disorder.

Therefore, we humbly propose the Cities Are Safe and Affordable Act, or CASA.

CASA is a single legislative bundle that addresses the two primary causes of American housing cost as a package: crime and anti-density housing policies. It is a grand bargain with something for everyone: law and order for the right, urban density for the left. These two concerns are fundamentally inseparable and must be addressed together. They are two sides of the same policy coin.

The basic framework of CASA is to introduce new federal mandates to reduce crime and increase new multi-family housing construction. These mandates include a new batch of minimum-sentencing guidelines specifically targeting the serial offenders who commit such an outsized proportion of crime. Crucially, it would require sentences of rapidly escalating length for repeat offenses not only for felonies but for certain misdemeanors, since so many blue states have recently reduced the severity of quality-of-life crimes like shoplifting, vandalism, and drug-dealing. For housing, CASA requires each state to demonstrate that each of their three largest cities took one or more steps to make housing more affordable: building a certain number of new units; reducing the median cost and length of the permitting and inspection process to under a new federal benchmark; eliminating low-density zoning in a certain proportion of the city. Or cities can obtain a waiver by showing median rents are dropping in real terms, proof that there is enough housing regardless of any policy choices made.

To get states to agree to these new requirements, CASA dangles an amount of strings-attached federal money they will find impossible to turn down. The federal government cannot of course mandate criminal penalties or housing policies in any particular state. But they can dictate that states which fail to adopt such reforms become ineligible for federal aid packages, such as the new construction loans and other subsidies that will be part of CASA. This is the same approach famously employed during the Reagan administration to compel states to raise the drinking age to 21, and has already withstood constitutional challenges. The states have the disadvantage of only being able to spend what they raise in tax revenue, but the federal government has no such restraints. It can and should use the power of the purse to break through the logjam of local inaction on density and crime in one stroke, with a carrot-and-stick approach to both problems.

In exchange for adopting anti-crime and pro-density reforms, CASA rewards states with generous block grants. On the housing side: tens of billions of dollars of zero-interest loans for housing developers building new multi-family housing in cities with rapidly rising rents, a massive supply-side subsidy that would kick off a building boom throughout the country. For the states themselves, a separate but equally massive fund will be made available to spend on whatever vaguely housing-related or economic-justice projects they might want to pursue, giving plenty of leeway to squeeze different pork-barrel projects in to make the money harder to turn down. On the crime side: new anti-crime block grants ensure states wouldn’t have to shoulder the increased criminal justice spending on their own. These grants would offset the cost of beefed up policing forces and prosecution, as well as finance the construction and staffing of new prisons. The federal government could also build and run prisons of their own in cooperation with the states, taking advantage of the much lower cost of prison operation in states like Mississippi and Arkansas relative to California or Massachusetts.

What might the cost of this proposal look like in absolute terms? First, let’s look at current home construction budgets nation-wide. As of September of 2025, the US was on pace to spend $419B building new single family homes, and only $113B on multi-family development. By means of direct comparison, in 2025 the US spent $36B on section 8 housing vouchers. The same money directed to zero-interest construction loans and grants would represent a 30% increase in available funding for new multi-family buildings.

And the cost of this new legislation could be significantly offset by eliminating the mortgage interest deduction, which has already become irrelevant to the vast majority of middle-class homeowners since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act increased the standard deduction to well above what most homeowners pay in mortgage interest. Doing so would raise tax revenue by around $30B per year on top of the reforms included in TCJA, and by over $100B per year if those reforms aren’t extended.

But, I’ll be honest: costs are not top of mind as I write this essay. Entitlement programs are going to eventually overrun the federal budget without massive reforms that we seem incapable of reaching in our current polarized climate. I have some amount of faith that the US will survive that storm when we’re finally forced to confront it, but the total lack of serious discussion about that looming problem makes the current administration’s fiddling on the margins of discretionary spending seem petty and vindictive. Trump’s budget proposal for 2026 would cut section 8 voucher funding and replace it with state block grants for rent assistance, resulting in a total reduction of spending of around 60%, saving around $20B. This is a mistake — that money should be redeployed, not simply cut. Trump and his allies should wield the power of the federal government to achieve the policy outcomes they want, rather than abdicating it. Instead of reducing entitlement spending by such relatively paltry amounts, to be lost in the coming budget crisis from Social Security and health spending, they should redirect such money in pursuit of policy goals they care about, such as reducing crime and housing costs for young Americans.

Oscar Wilde quipped that a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing. The idea of massive, new federal spending is enough to make many on the right blanch. But unlike most federal spending, we would not be simply pouring it into a bottomless pit of entitlements — we would have a lot to show for it, in the form of cheaper housing and safer cities. Those things are worth having. They’re worth spending money to obtain, even at the cost of accelerating our looming debt crisis. And the federal government is uniquely capable of spending money to obtain them.

I honestly think we need to get serious about diffusing demand in high CoL metros by just de facto building new towns and cities as a sort of 21st century hybrid of company towns and Soviet “science cities” like they built in Siberia. You mentioned the Feds building a handful of offices in dying rust belt towns, which I agree is an inadequate solution, but I think they need to get a lot more radical with the approach and offer huge financial incentives to corporations to locate high tech manufacturing in these areas while simultaneously fast tracking and incentivizing residential and commercial construction and redevelopment, build the needed infrastructure to support a future larger population, and make it desirable to open tons of small businesses like restaurants, bars, and shops of the sort that younger urban professionals like. You can’t just half ass it on this, it’s got to be a coordinated private and public venture to rapidly create new cities of the type middle class people actually would want to live in.