The feminization is coming from inside the house

Laws aren't to blame for the Great Feminization, we are

Thank you to the many loyal readers who drew my attention to The Great Feminization by Helen Andrews, published in October in Compact. Presumably they were inspired to reach out by my pinned tweet.

I’m late to the party on this article, so lots of ink and invective have already been flung back and forth. If you missed it, take the ten minutes and read it, it’s worth the time. But as my pinned tweet implies, I think it’s probably beyond dispute that this feminization has occurred, and that this is a very consequential development. Andrews explains why:

Everything you think of as wokeness involves prioritizing the feminine over the masculine: empathy over rationality, safety over risk, cohesion over competition.

…

Female group dynamics favor consensus and cooperation. Men order each other around, but women can only suggest and persuade. Any criticism or negative sentiment, if it absolutely must be expressed, needs to be buried in layers of compliments. The outcome of a discussion is less important than the fact that a discussion was held and everyone participated in it. The most important sex difference in group dynamics is attitude to conflict. In short, men wage conflict openly while women covertly undermine or ostracize their enemies.

Any casual observer old enough to remember life as late as the 90s can think of a dozen ways this process has manifested in their own lives. It’s much harder to think of counter-examples to this general trend, although people of course try. But on the whole I just don’t think there are many good-faith objections to the fact of the Great Feminization. Rather, people are left arguing about one of two things:

Is it actually Good that this is happening? Maybe the dysfunction we observe in every institution that becomes female-dominated is actually caused by something else. Or maybe it’s the case that what we perceive as dysfunction is just the pain of a paradigm shift, that we’re in the middle of a realignment of values that will ultimately lead to a better world.

No, it’s Bad, actually. Whose fault is it?

Andrews addresses both of these questions. As to the first, whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing, she writes,

The problem is not that women are less talented than men or even that female modes of interaction are inferior in any objective sense. The problem is that female modes of interaction are not well suited to accomplishing the goals of many major institutions. You can have an academia that is majority female, but it will be (as majority-female departments in today’s universities already are) oriented toward other goals than open debate and the unfettered pursuit of truth. And if your academia doesn’t pursue truth, what good is it? If your journalists aren’t prickly individualists who don’t mind alienating people, what good are they? If a business loses its swashbuckling spirit and becomes a feminized, inward-focused bureaucracy, will it not stagnate?

As to the second, whose fault it is, Andrews places the blame on social engineering and civil rights law:

Feminization is not an organic result of women outcompeting men. It is an artificial result of social engineering, and if we take our thumb off the scale it will collapse within a generation.

The most obvious thumb on the scale is anti-discrimination law. It is illegal to employ too few women at your company. If women are underrepresented, especially in your higher management, that is a lawsuit waiting to happen. As a result, employers give women jobs and promotions they would not otherwise have gotten simply in order to keep their numbers up.

This is basically the same hypothesis laid out in 2023 by Richard Hanania in his book The Origins of Woke and taken apart by Scott Alexander in his review. Hanania focuses more on race than gender, but it’s the same argument: the cultural changes we now call wokeness are downstream of the ever-ballooning set of contradictory workplace requirements we call civil rights law. Andrews sees the institutional and cultural dominance of women as the ultimate cause of the turn to wokeness , but also traces such dominance back to civil rights law.

But this explanation is unsatisfying. Alexander writes:

Even the book’s own history of the civil rights movement seems to undermine its thesis. This history, remember, is that Congress tried to pass reasonable and limited laws, and then woke activist judges and bureaucrats kept expanding them into unreasonable power grabs. And that (he says) was the origin of wokeness. But if a movement has captured the judicial branch and the civil service, it seems like it must have already originated. Grant that this was an older form of wokeness more clearly grounded in the anti-segregation struggles of the 1960s. But that just brings us back to the question of where the new 2010s version of wokeness came from, which the book also doesn’t answer.

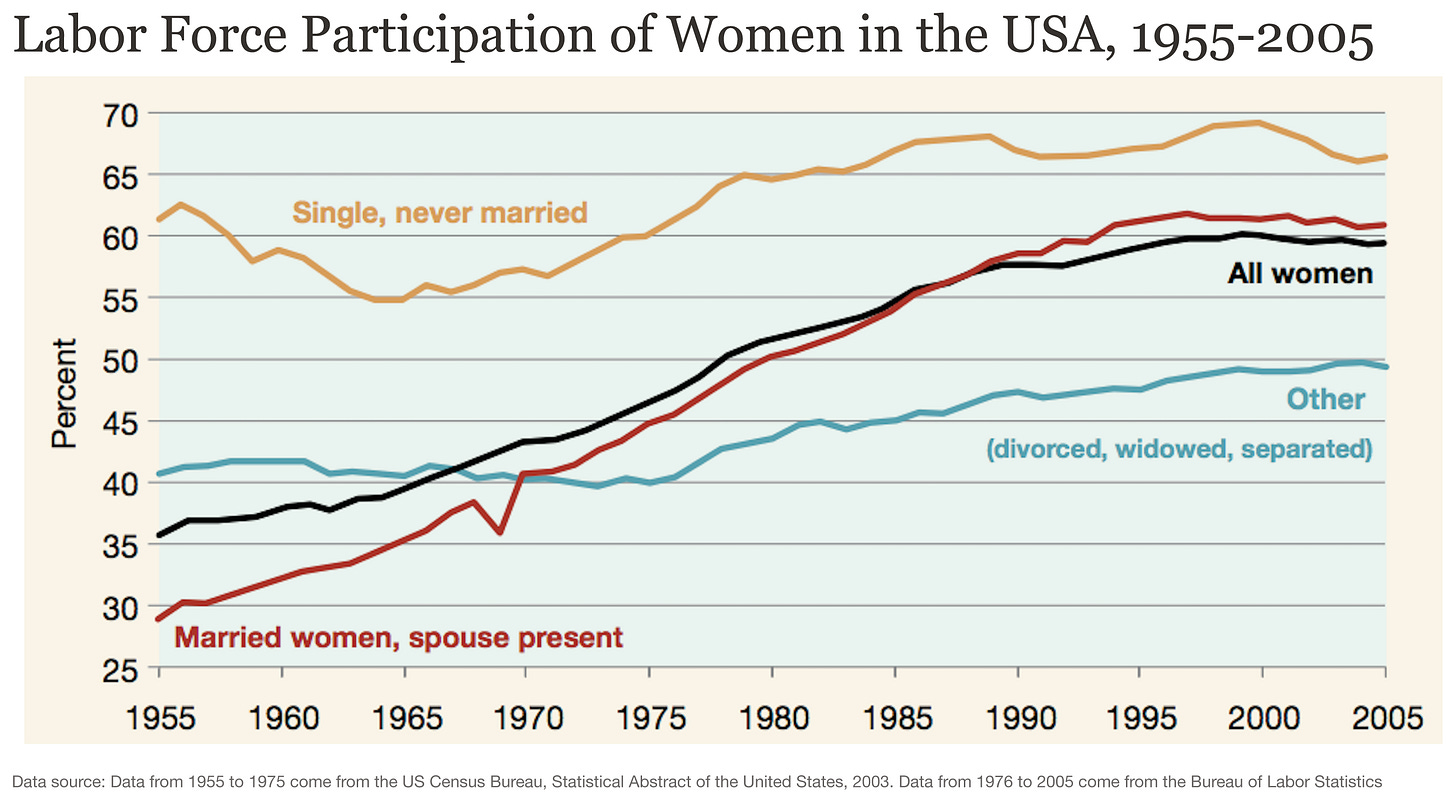

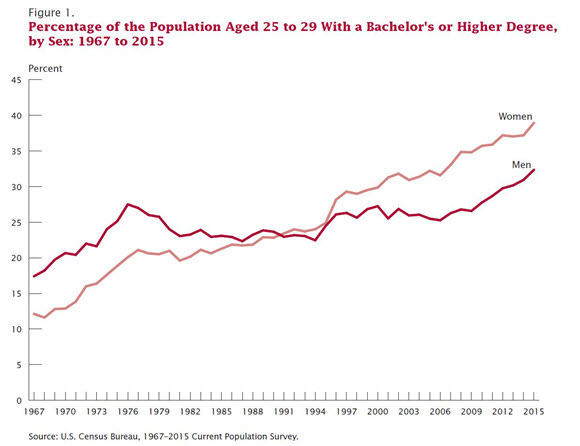

I’m here to agree with Alexander and disagree with Andrews and Hanania as to the cause of wokeness and the Great Feminization. Politics and law are downstream of culture, not vice versa. And western culture has been feminizing and liberalizing for at least the last few hundred years. Choose any long-run trend relating to culture — whether it’s eligibility to vote, birth rates, literacy, non-farm labor participation, graduation rates, violent crime, take your pick — and you will observe steady, gradual change since the dawn of industrialization, all in the same direction. There are shockingly few lines of delineation marking the passage of particular laws, or supreme court rulings, or the outcomes of elections. What we now call wokeness or the Great Feminization are simply arbitrary labels that we place onto these very long-running trends.

Where on the above two charts did the Great Feminization occur? It’s a trick question: neither of them go back nearly far enough. It was already well underway by 1955, long before the civil rights act and the EEOC were more than a twinkle in a young communist’s eye.

Let’s approach it from another angle. The second chart demonstrates that women became a majority of new college graduates by 1990. Why, then, have we constantly heard since that time that women face unfair discrimination in higher education, that we must level the playing field with scholarships and programs targeted at increasing women’s college participation? Do people not understand women already out-perform men in college graduation?

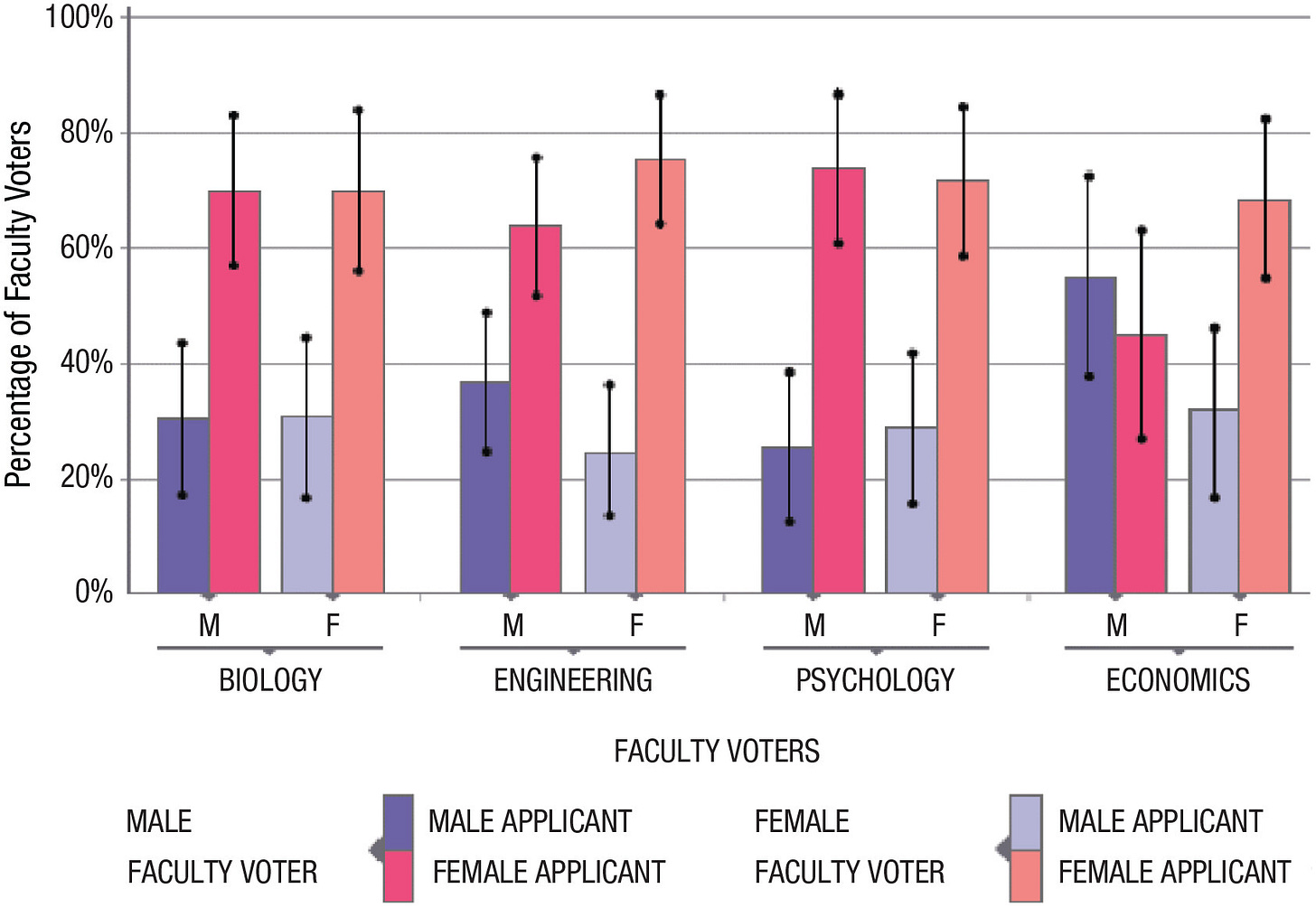

In most cases, they do understand that, at least at some level. But on a more visceral level they still feel that women are simply more inherently worthy of our attention and resources than are men, a bias shared by essentially everyone throughout the West. There are good reasons to believe this bias is simply baked in through the process of biological and cultural evolution — women are the bottleneck to reproduction, and any tribe or culture which didn’t elevate their needs above men’s got out-reproduced and therefore outcompeted by those who did. But we have empirical, quantified evidence of the phenomenon since at least 1994, when the “women are wonderful effect” was first coined. Despite what activists might claim, women’s needs are on the whole given more attention than men’s, and in general people like women more, want to be around them more, want to give them considerations and privileges above and beyond what’s afforded to men. Steve Stewart-Williams just published this graph detailing the large advantage in hiring enjoyed by women across a variety of fields in academia:

Both men and women very strongly preferred female candidates with identical on-paper qualifications, and this was true both in fields that are male-dominated (engineering) and female-dominated (psychology). Nobody in a psychology department is worried about running afoul of a lawsuit for not hiring enough women, but they still prefer female candidates by at least 2 to 1. (The sole exception was male economics professors, and even there they barely split in favor of men, within the margin of error).

So it’s easy to demonstrate that preference for women far exceeds what is required by civil rights laws. It would be foolish to claim that such laws didn’t accelerate the process, and it’s also easy to find cases where overzealous application of the laws produced perverse and lopsided outcomes, e.g. the elimination of some men’s sports programs under Title IX due to too few women being interested in fielding a team. But on the whole, I subscribe to a bigger-picture view which considers civil rights laws and social feminization as both being part of the same process, driven by cultural and technological changes. The law is as much effect as cause.

My own personal experience with these changes has been working for elite tech companies over the last twenty-something years, and I tend to specialize in especially gear-headed domains where the male-female ratio is even more lopsided than in tech as a whole. I’ve seen first-hand how the behavioral norms of an organization shift as women go from being more than a token minority to even a small minority. The famed “boys club” of tech, the “frat-house” environment so decried by women’s activism in the mid-2010s, is a real thing. I saw it first hand. But only on teams where there was, at most, one or two women, and they were “one of the guys.” As soon as there were even three women, even on a team of dozens of men, the behavioral norms shifted abruptly to what women preferred. Out: nerf gun fights, push up contests, casual put downs, practical jokes. In: listening, collaboration, small talk, implicit social status games. Nobody had to be threatened for this change to occur, certainly not by lawsuits. Even computer nerds, famously socially blind, quickly adopt more feminine norms when women enter a social space. And the point at which this happens is nowhere near the 50% female Andrews implies is required. It happens as soon as there is any visible group of women, almost no matter how small. Their preferences are instantly afforded more consideration than men’s by tacit consensus.

Civil rights laws that apply to schools and the workplace cannot explain the feminization we have witnessed in all arenas of society. They can’t explain why boys getting in fights went from being a rite of passage to an almost unbelievably gauche catastrophe involving therapists and lawyers. They can’t explain why 80% of animated feature films released in the last decade have a girlboss protagonist. They can’t explain why playgrounds have been systematically neutered, or why free-range children get policed called on them. And they can’t explain why women are responsible for 80% of fiction book sales, or why so few publishers appear interested in men’s reading preferences.

Personally I place a much greater emphasis on evolving cultural attitudes, changes that have shifted our shared understanding of virtue away from masculine strengths — thing like hierarchy, competition, and reason — toward feminine strengths such as empathy, collaboration, and nurture. The people driving these changes are not by and large pressured by lawsuits, although those play a role on the margins. Rather, they prefer the feminine virtues because they genuinely favor women’s social norms over men’s, and because they are true believers in a progress narrative that insists women are permanent underdogs who need special consideration and favoritism in every process. Women’s concerns get more attention because of our biological and cultural predisposition to care more about them: women's tears win in the marketplace of ideas. Simultaneously, technological changes in how we produce value for one another in the real marketplace of the economy have placed a premium on those same feminine virtues. Today, the primary measure of merit during childhood and adolescence is being able to sit quietly, focus on boring work, cooperate with others, and conform to social expectations. It wasn’t a false “social engineering” experiment that produced these changes, but a real response to real changes in the nature of work and value production.

All of these factors pull in the same direction, toward feminized social norms. There’s no magic bullet, no law or set of laws we can repeal, to shift them the other way. And many of the people agitating for such changes wouldn’t like the result. Talk to somebody who went to high school in the 70s or 80s and they’ll tell you the most horrific stories about fights and bullying, events that used to be taken for granted that we now consider exceptional. Or ask someone who worked a corporate job in that era about the kind of abuse and harassment they had to endure from superiors before HR departments existed. Relatively few people would take the deal to return to those conditions. In a very real sense, the process of feminization is the process of domestication, of enabling the human animal to get along with others of our kind in the increasingly large and complex social systems that we build.

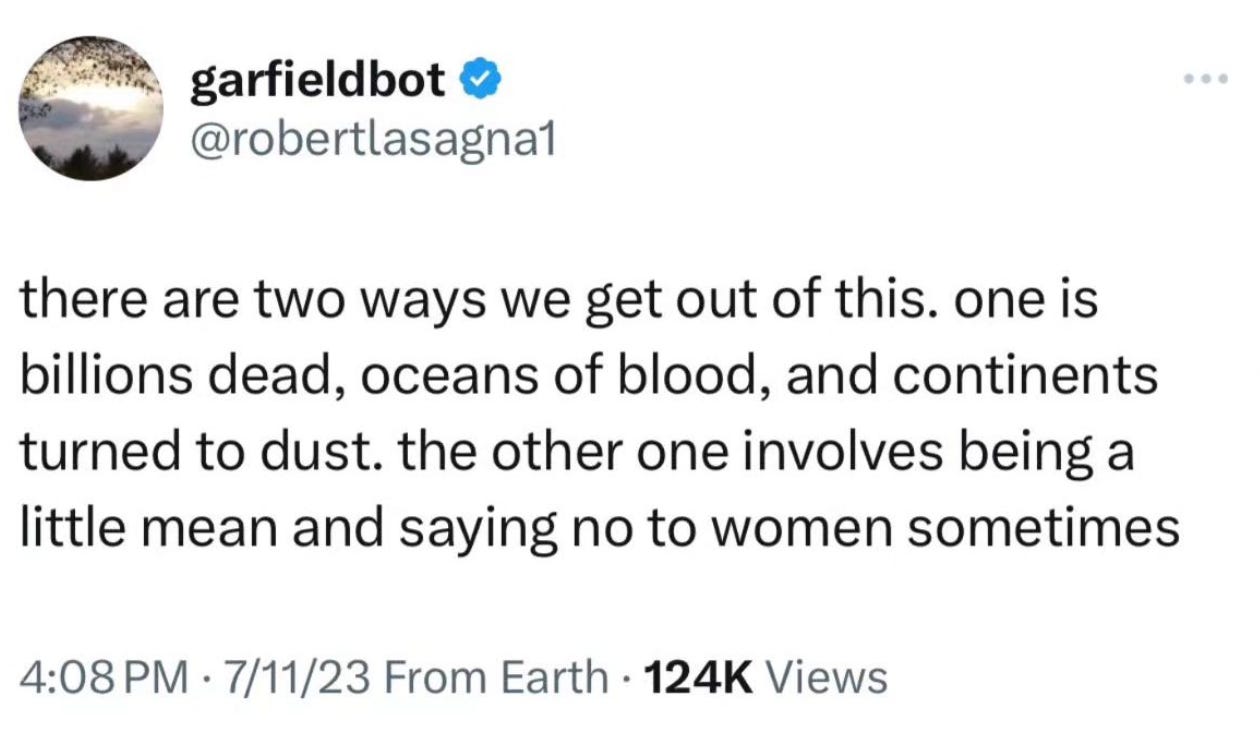

The question is what natural limits this process might run into, what checks on its continued elaboration into the realm of the absurd might exist. Andrews worries that the feminization of the legal system in particular represents an existential threat to Western civilization’s standards of objective justice, and I struggle to raise a real objection. But I also struggle to imagine a future where such an absurd collapse doesn’t come to pass eventually, not as a sudden event but as a slow and unequally distributed decline that we began decades ago. A society that manages to reverse it wouldn’t much resemble the one we live in, a society that I love despite the increasing weight of contradictions it must carry to function at all. A sudden turn to religious nationalism ala The Handmaid’s Tale remains the mad fantasy of fetishists, not a genuine possibility in our civic evolution. The same is true of half-trolling calls to #RepealThe19th — the society that would do such a thing bears little resemblance to our own, and you wouldn’t like living in it. And in any case, who do you think voted to pass the 19th Amendment in the first place?

And yet, it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that the trend of feminization can’t go on forever. Therefore, it won’t. I don’t know what will break first or how, only that there are no simple answers. And that something has to give.

Western men, post WWII American men particularly, have built societies so long safe, predictable, equitable, free, and comfortable, that women are afforded the luxury of imagining that men and masculinity are no longer necessary. Even that men are the only impediment to the utopian world they now have the unencumbered time to envision.

But there is a world outside of our Western bubble that is violent, driven to conquest, and interested only in expanding its own power. The more feminization weakens the West internally, the greater the danger we will be overwhelmed by reality outside of that bubble. Should that happen, and I don't see how to stop it, women's concerns about glass ceilings, workplace harassment, shared housework, and affordable childcare will fade into the rubble and terror as they cower and wonder who will protect them now?

The most infuriating part of modernity is the ambiguity of authority. Men can tolerate a superior who is a bit of an asshole, but they despise being mistreated by an invisible force they have no redress of grievances against.

Also, while I agree with your point the great feminization far preceded Civil rights law, and there is a biological force in play, it also made all-male spaces, often even private ones, illegal. There was a men's social club in Detroit that was forced to open itself up to women because big business deals were made there. Also, it's illegal to have exclusively male team once your business reaches a certain size. Civil Rights law didn't start this, but it's making sure it gets no competition.