There was a war on Christmas

Christmas lost

Happy New Year. I hope your Chrismastide was as joyous as my own.

But as happy as the screams and laughter of the kids were, my own thoughts were, as ever, darkened by discourse. Since reading it a few weeks ago, I’ve been ruminating and reflecting on Drunk Wisconsin’s essay Christmas is a secular holiday. His thesis is that Christmas’s religious origins are now mere historical curiosity, and that the actual holiday, as celebrated by actual Westerners, is completely secular. Consider the extreme outsider view:

An alien lands in the middle of the US in December and starts learning about Christmas. Superficially, Christmas is about lights hung on the outside of single family homes, Christmas trees decorated with ornaments, and wreaths hung on doors. It’s about familiar Christmas music getting played on repeat and Christmas movie marathons at night. It’s about buying presents for your loved ones, particularly kids. There’s deep lore behind common Christmas characters: Santa Claus delivers presents to kids on Christmas night by landing his reindeer-pulled magical sleigh on their roof and coming down the chimney, his lead reindeer is a bully victim named Rudolph with a glowing red nose, he lives at the North Pole and has elves help him make toys all year long, he keeps a list of naughty and nice kids, and sometimes his wife makes an appearance, particularly when it’s a movie about his origins.

Once you get past that surface-level stuff, Christmas is really about cozy winter vibes and curling up in front of a fire place with a mug of hot cocoa, even if the fireplace is on your TV. It’s about nostalgia for the Christmases of your youth, listening to the same songs that have been played for generations, and watching comforting movies with a joyous moral message. It’s about family, about parents and grandparents watching the sparkle of youthful naivety in their kids’ eyes as they see the presents Santa left them under the tree on Christmas morning. It’s about embodying a Christmas spirit, about Christmas magic, about something that extends beyond the physical and feeds the soul.

Having learned all of that, I would say the alien understands Christmas. If he is a particularly thorough student, he might dive into the origins of this holiday and may be surprised to find out that Christmas is a specifically Christian religious holiday. It turns out that this holiday isn’t about coniferous trees or presents or Santa at all; it’s about the birth of Jesus Christ, the god-messiah of the Christian faith. It turns out that none of the stuff he learned about is relevant to Christianity at all, and that no official Christian church requires its members to decorate their houses in lights or set up a tree or pretend reindeer can fly. Only having learned this does he look back and admit that there are some religious elements peeking through here and there in all of that consumed Christmas content.

The typical American who celebrates Christmas, even if they are Christians who attend church on occasion, do not primarily celebrate the birth of our savior. They celebrate a secular mythos of Santa and reindeer, of family togetherness, of gifts and generosity. Jesus may make an appearance, but he’s a footnote, not the main show.

Of course this observation is nothing new. Devout Christians have been complaining about the secularization of the holiday for so long that it was already a punchline in the early 90s, in the Dana Carvey era of SNL.

That battle having been conclusively lost, the religious right retreated to a much weaker grievance, which itself has been so widely lampooned that it too mostly serves as a punchline among bien pensants: that there’s a “War on Christmas”, a distributed campaign of erasing public celebration of Christmas in favor of a generic “holiday season.” Usually people grinding this axe will point to examples in commerce and media, whether that’s Starbucks printing a different message on their seasonal merchandise, or the local news affiliate dropping traditional coverage of Christmas celebrations such as tree-lightings. Governments have additional reasons to tread lightly here given the capricious nature of first-amendment litigation, which is why public schools now grant a Winter Break and nativity scenes on government property are rare. There are too many examples to point to individually, and it’s easy for casual observers to convince themselves that public, communal celebrations of Christmas are in steep decline, even if far from extinct. The Christian faith and the Christmas holiday in particular are no longer ubiquitous, near-universally shared cultural assumptions, as they were even a few decades ago.

The War on Christmas is a frustrating front in the culture war. It’s at once obviously, undeniably taking place, but prosecuted in such a way that responsibility is murky and diffuse, no one in particular to blame. It’s also clearly not the case that public celebration of Christmas, by private actors, has been in any way meaningfully curtailed or outlawed — you can tell your coworkers and neighbors Merry Christmas, you won’t get fired or sued.

And yet. There clearly was a War on Christmas, and Christmas lost. People complaining about what people write on their end-of-year holiday cards or on their coffee cups are fighting a war that was conclusively decided decades ago, and most haven’t seriously reflected on this fact. The Christmas they seek to save, the second-most important religious holiday for what remains a massive majority of Americans, has already been strip-mined of religious significance in popular culture, its meaning hollowed out, its celebration crassly commercialized. The war is over. Christmas lost.

I can’t speak for the experience of older people, but my generation has a hard time even recognizing the decline. The war was more or less over by the time we were born, and the Christmas culture we grew up with was already thoroughly secularized. Over Winter Break, my wife and I bought a few moments of relative peace and calm by showing the kids a classic TV special from our childhood, A Muppet Family Christmas. It’s available on YouTube in full, so you can watch it if you’re curious or in the mood to reminisce. On the whole it’s a very solid Muppet special, fun for the whole family. But I found it very revealing, on rewatching as an adult, how far the slide to secularization had already advanced by 1987.

All the Muppets come out for the special, with the original cast of The Muppet Show getting joined by the Sesame Street gang and even the Fraggles. At one point Kermit and his nephew Robin find an entrance into Fraggle Rock, where they explain to the Fraggles what Christmas is. It takes place at around the 32 minute mark in the special.

Don’t you have Christmas? [Robin asks the Fraggles]

That’s when you gather together with the people you love and you wish each other peace on Earth.

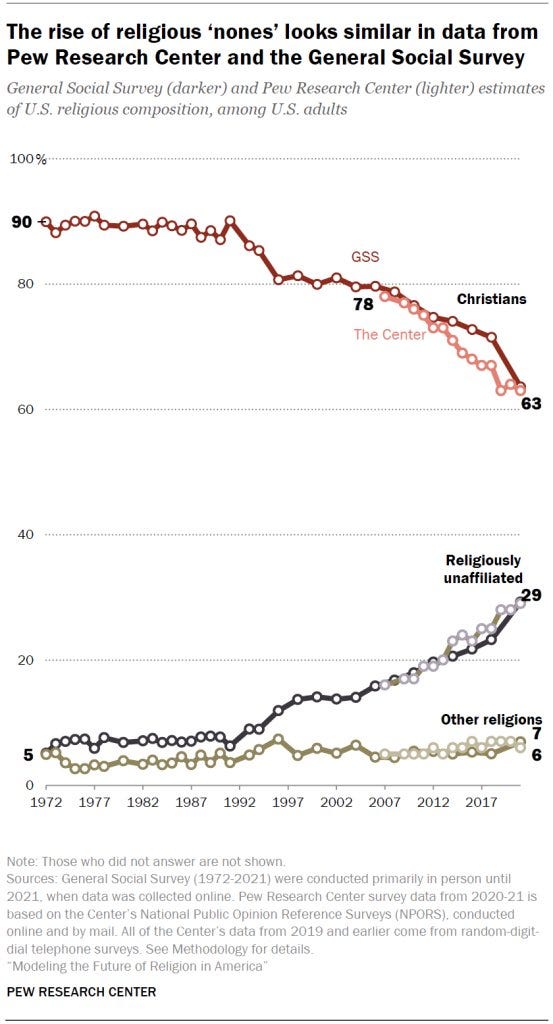

While it’s pretty funny to imagine the alternate-reality Christian version of this story, with a missionary Kermit solemnly explaining to the heathen Fraggles that a Savior was born whose death and resurrection would lead to the forgiveness of sin and the establishment of a new and eternal covenant (“What’s sin,” Gobo asks), that kind of network media was already essentially extinct by 1987. And it wasn’t because the practice of Christianity was on the wane, at least not yet. At the time of broadcast, around 90% of Americans were church-going Christians.

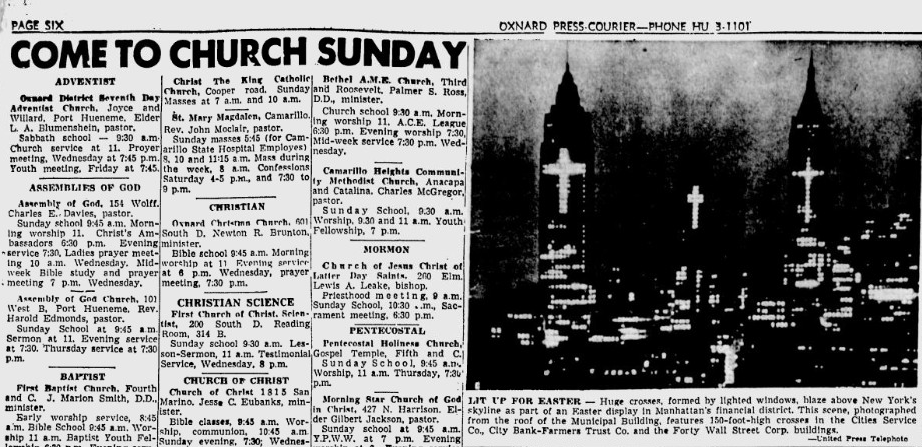

If mainstream Christians in 1987 objected to the omission of Jesus from a Muppet special, and indeed from most popular media, I sure don’t remember it. My own parents were probably about as devout as most nominal Christians of their generation, and while they made sure their children understood the religious significance of Christmas, they also didn’t put up much of a fight when it came to media that downplayed or completely omitted that meaning. We watched the Muppet Family Christmas, we watched The Santa Clause, we watched The Grinch. My parents, like most in their generation, didn’t see any harm in it, and why would they? The grew up with Christmas media that looked like this:

As for the popular Christmas songs they enjoyed as children (and which still comprise the canon today): enough has been said. But none of them are about Jesus.

Strangely enough, the same generation that ushered in this secularization of Christmas in popular culture themselves grew up in a culture awash in explicitly religious pageantry around the Christian holidays, and around Christmas in particular. Religion played so large a role in their day-to-day lives that most of their grandchildren would find it off-putting. They prayed in public school and read the Bible there, as well as at home. Their town hall probably had a large, publicly funded nativity scene. Their community life was organized around church membership and attendance. And unlike today, no one was particularly furtive about proclaiming their faith to the world in a professional context, as in this now-famous photo of Manhattan skyscrapers turned into giant crosses for Easter.

The War on Christmas was lost so long ago that most of us discussing the topic today don’t even really understand how radically different our understanding of the holiday is compared to that of our forebears of even 80 years ago. We are fish with no idea what water is. The concept of a devoutly religious Christmas, universally celebrated with worship, feels like a legend of another age long passed. Instead we are left with a cargo cult of Christmas, a popular culture and media environment that yearly goes through the motions of celebration with no real understanding or shared agreement what it all means or is meant to accomplish. We’re left with cultural Christianity, but no religious feeling to accompany it.

And it’s not just Christmas, either. Once you notice this trend you see it everywhere in media and culture, as when our family recently watched the third Harry Potter movie. This is the entry in which Sirius Black is revealed to be Harry’s godfather, which implies that Harry was baptized in the Church of England (or perhaps in some parallel wizarding church). Of course we already knew that Christmas exists to the wizards of England, seeing as they celebrate it at Hogwarts with great fanfare, exchange gifts, and so on. But the fact that Harry was baptized implies something far stranger and wilder: that the wizards are Christians, that they believe in God and, one assumes, the resurrection and the forgiveness of sin. But what’s even stranger is the total nonchalance with which Rowling treats these implicit facts, their curious lack of bearing upon the greater mythos of the fictional world or the plot of the books. You might wonder if Jesus was himself a wizard in the modern wizards’ understanding, or ponder any number of other thorny theological questions as they relate to fictional magic. But it’s clear that Rowling did not, that to her the act of baptism carries about the same significance as a quinceañera. And so it is with many of her generation, and those of use who came after.

More than anything, I find this topic disorienting to think and write about. The waning importance of religious faith in our shared customs is hard to even form a judgment about when one has been steeped in it for one’s entire life. What would it be like to be part of a community, or a broader culture, that took the Christian holidays seriously, as a matter of eternal life or death? What would it be like to participate in a society-wide religious holiday that actually had religion at the center of it? Other cultures surely still understand this feeling to a greater extent than my own. But I’m an American, and in our culture, the Christian holidays are secular, even among most believers.

Our family has for the last several years attended vigil mass on Christmas eve, which has quickly become a beloved tradition for us. Our church does a lovely service, and you have to arrive early: the pews are completely packed a half hour before the opening rites, with overspill seating in adjacent buildings. But this is an anomaly that in no way reflects attendance on a typical Sunday — most of the attendees are strangers to us, fellow parishioners we never encounter at regular mass. Are they Cultural Catholics, going through the motions of a tradition for its own sake? Will their children take their place when the time comes?

Will mine?

The truth of this is made especially clear when you see supposedly “conservative Christians” on X angrily condemning “Santa deniers”. As recently as forty years ago I remember especially devout elders at my church sharply pointing out that Santa was not real and that the Santa cult was undermining the religious message of Christmas. Yet today no one is more dedicated to the secular Santa-isation of Christmas than conservatives.

A Charlie Brown Christmas is explicitly about the birth of Jesus. It came out in 1965, 22 years before the Muppet Christmas.