I dick around

Chronic inability to lock in is not recognized by the DSM-5

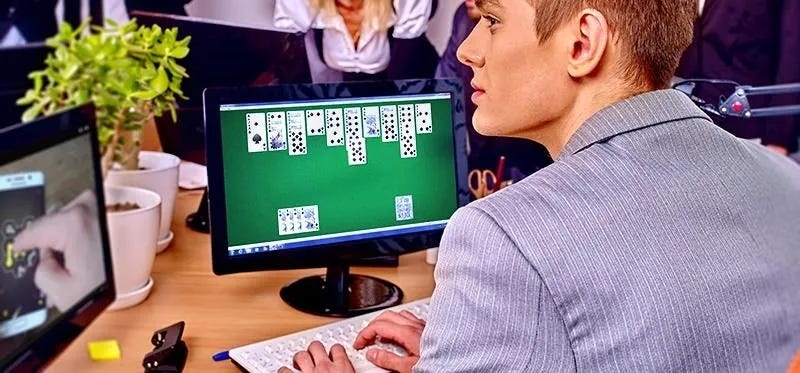

Walk around the physical offices of any computer job. Wear sneakers so the laptop jockeys can’t hear you coming up behind them. Look at what’s on their screen before they notice you standing there watching. What will you find?

In a large number of cases, you’ll find social media, or YouTube. You’ll find personal email, or shopping sites. You’ll find random articles on the New York Times. You’ll catch a lot of people staring down at their phones, presumably not for business purposes. You’ll find lots of Slack or Teams or forum posts that have next to nothing to do with work. You’ll even see a surprising amount of video games and porn, if you’re sneaky enough.

What you won’t find is concentrated, heads-down work on primary business goals. Not for a majority of office drones, for a majority of the time. And if you listen to conventional wisdom on this point, this is normal and fine. It’s unreasonable to expect eight hours a day of concentrated, creative work. Maybe five, if you’re lucky, but three is more realistic. The rest will naturally get filled in with chit-chat, little mental breaks, naps, what have you. In short, there will be a lot of dicking around.

I work in software, and this general rule seems to hold there as in other domains. But over the years I’ve met a few engineers that aren’t susceptible to the malaise. Through some arcane mixture of personal virtue and righteous habits, they seem to possess a supernatural ability for deep, focused work for an entire eight-hour workday. Every time I walk past their screen, I see code or documentation or a terminal. They are always on task, never dicking around.

Not me though. I dick around.

My bosses know this. My teachers knew it. I know it. Some of my earliest memories of doing homework involve not doing homework — instead drumming rhythms on my desk with pencils, looking out the window, or just daydreaming. (No phones or internet back then, so if you were working at a desk high-value distractions were a conscious cop-out instead of the default.) But I got my work done pretty much without fail, on time, at near perfect correctness. I just didn’t do it all at once, or on a straight and narrow track. I dicked around, basically as much as I could get away with.

These work habits carried forward into university. My discipline in spending time at a desk was exemplary, but my output lumpy, uneven, prone to deadline panic. I learned this about myself, that it was pointless to try to pace myself and spread out the work. I knew I was going to write a paper or study for a test the night before, so why bother starting any earlier? It would just be a frustrating waste of time. Much to the chagrin of group work partners, I would ignore their conscientious gradual check-ins and increasingly frantic requests for updates, cranking out my side of the work at the final hour with perfect aplomb and carrying the entire team with me. Even at the time I understood this to be completely insufferable behavior, but earning the team an A on the assignment bought me a lot of good will, at least in hindsight if not in the moment. Eventually even the night before seemed like too early to start work on certain assignments. I learned I could reliably write around 750 words of polished prose an hour, but only if every minute actually counted — so the morning a paper was due, not earlier.1

I graduated (with honors), and things changed but stayed the same. As teaching assistants sometimes reminded their undergraduate students, the classroom is not the real world, and much more would be expected of us once we graduated. This turned out to be only half right. Yes, the artificial structure of coursework, with regular assignment deadlines and numerical feedback, often didn’t obtain in a cubicle farm, where project work could be long and meandering, with months between milestones and relatively little supervision to keep you on track. But on the other hand: I found that in practice the bar was shockingly low, because everyone was dicking around or ineffective or both. Even spending several hours a day reading web comics and internet news from the comfort of my cube, my output easily outpaced the median member of my organization. And what’s more, I found that, in the real world, with real consequences that would bring real honor or real shame to myself and my team, real profit or financial ruin, I actually cared about my work for its own sake, not for the sake of simple pride or a fake grade. At least, most of the time.

Life is long, and motivation is so fickle. When you spend decades trading keystrokes for your daily bread, you go through weeks or months when nothing much seems to spark your genuine interest, but still needs doing. You’re still getting paid to do it, in principle, even if that pay is disconnected from your actual output. Urgent work is always pressing and leads to immediate feedback, and is always gratifying to perform for that reason. But an entire critical class of labor is vital but non-urgent, and as you become more experienced a greater degree of your focus is directed to this kind of work, and you are granted more autonomy, less real supervision. In this environment, a man prone to dicking around comes to a crossroads, at war with himself: can he push through the inevitable grinding, uninteresting tasks inherent in any long project to find the satisfaction of the meaty part of the work? Or will he rot on the vine in his prime, getting paid for nothing in particular? Dicking around.

Me, I dick around and war with myself. My output is still lumpy and uneven. I tweet. I read and cogitate on long think pieces. I manage my side hustles on company time. And then sometimes, often even, I really tear shit up, outdoing all the other quirked up white boys in busting down productive-style. When I’m on, I can outperform just about anybody I’ve met, the occasional 10x genius notwithstanding. But when I’m off, I can’t be bothered. And I often don’t know when I start a day or a week or a month which version of myself I will be. It can change suddenly for reasons I still find mysterious, often completely obliviously to the real-world, long-term importance of my work. I’m still great in an emergency, in the clutch. But most of a career doesn’t take place in the grips of panic, at least one hopes.

I have various coping strategies for dealing with this aspect of myself, some of which work more reliably than others. None is perfect. Some days nothing works. And then, some magic days or weeks or months, no coping is needed, everything is firing on all cylinders, the world is mine to command, including my own attention. I dick around on those days too, but my workstream glides effortlessly past those disruptions, a bubbling brook rippling over timeworn pebbles, unperturbed. And those beautiful golden days, their inevitable return even after the longest drought, reassure me that everything is fine, really.

And that’s good, because I have absolute faith another golden stretch will always be just around the bend to bail me out in the nick of time. But I also know it will arrive on its own mysterious schedule. And I’ll probably be dicking around when it gets here.

No, every minute does not count when writing these essays. I’m trying to figure out how to change that productively.

I often joke with a close friend and colleague that on any given day I flip between astounded that I get paid so much given the amount of screwing around on company time I do and furious that I am not paid more considering my relatively high output compared to peers.

We are the opposite of middle school colour coded binder girls. My notes are disorganized if they even exist. I don't know where we are on the gant chart for this project. And yet in every crisis the boss airdrops me in to fix it.

They need to make an ozempic for locking in that isn't meth.

There's a dicking around sweet spot one needs to hit. Many of the guys grinding a full eight hours are doing pointless busywork or doing it wrong. Think the guy who goes through the same 20 steps several times a day instead of spending an hour to write a proper script. There's also the guy who checks in shit code because the problem was more difficult than he thought and he procrastinated till the end.

I've known a few who can keep heavy focus on complex topics for eight hours, and those are the expert analysts that could pocket 400k a year easy. Regrettably, those are also the ones companies underpay compared to the "dick around" guys. For all their impressive concentration, they also tend to be pushovers.

My most amusing experience was when I finished my work for a scrum a week early and asked the lead for more work. He hesitated because he was afraid of the charts looking bad if I didn't get the new task done by the end of the sprint. Message received sir, I'll dick around.