Over the hill

On going the way of all flesh

At 27 I had already noticed my decline. Wrestling with a difficult engineering problem at work, I would recall learning calculus and physics at 17 and ask myself, wasn’t it easier then? Didn’t my thoughts come faster, nearly unbidden, didn’t they flow without effort? Not like now. I could feel the mental gears grinding under load, resisting me, sand between the teeth. Not enough lubricant, or too much wear. Was it just my imagination, or was my lamp starting to dim?

True, I had spent the intervening decade punishing my brain cells with a variety of substances licit and illicit, some of which must have left a mark. I would sometimes look at my Mormon colleagues with wry admiration, reflecting enviously on the growing cumulative substance abuse gap that separated us. Here I had been stewing my fragile neurons in a toxic soup of feel-good chemicals while they chastely labored for their own improvement and the glory of God. What kind of freak does that, I groused internally.

It was cope, of course. Even at 22, regularly taking eight beers and a bong rip straight to the frontal lobe of a Thursday evening, my total intellectual output was higher and more easily coaxed than it would be just a handful of years later. At 20 I taught myself to play guitar well enough to get laid while taking a full college course load, working part time, and partying two or three nights a week. At 28 I struggled to find the energy to do more than push play on the new Netflix DVD after work most evenings. What happened to my youth, could it really be spent so young?

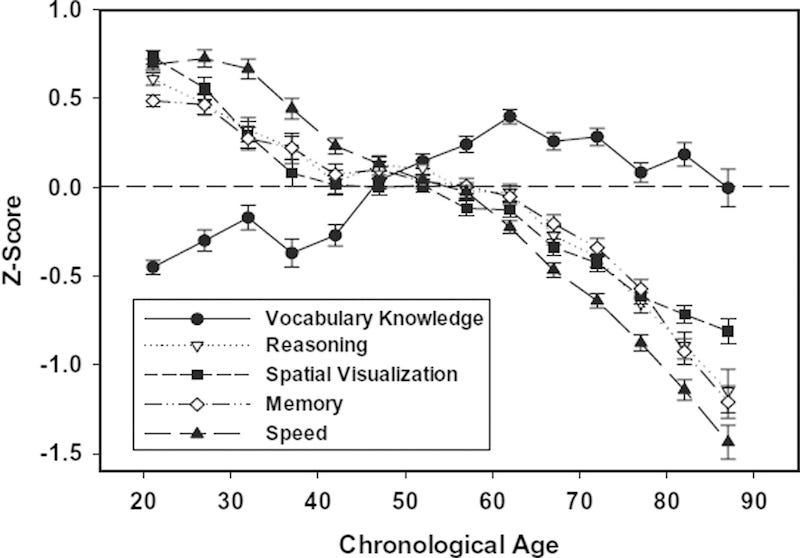

We tend to think of cognitive decline as something that affects the elderly, the Bidens and Trumps of the world, not men and women in their prime. But this is wishful thinking. We don’t start classifying decline as such until it reaches some threshold of reduced capacity that both of our last two presidents were obviously on the wrong side of to varying extents. But this threshold classification scheme conceals an underlying reality of steady, near-linear decline from a young age. The uncomfortable truth, established by countless studies, is that raw cognitive power peaks early in life and declines steadily until death.

The decline I began to notice in my late twenties wasn’t my imagination, and it didn’t stop then. The decades since have continued on the same trajectory — I look back with wry envy at the 27-year-old concerned he was already past his peak. He wasn’t wrong, but he couldn’t understand how far he had to slide. I would pay a lot of money to be him again.

I’m simply not as sharp as I once was. It takes me longer to learn new things, to understand and choose the best course of action from the options in front of me. I tire out more easily. I’m slower, more prone to being derailed by interruptions and wrong turns. I can’t work through the night or power through a hangover like I used to. I’m getting old, and the worst is still to come.

But if I’m older and slower, surely I’m also wiser. What of the countervailing effects of life experience, the accumulation of skills and knowledge? Don’t those offset the decline? Yes, a bit. Tanner Greer notes that unlike measurements of raw cognition, career achievement among intellectuals tends to peak quite a bit later.

In most fields creative production increases steadily from the 20s to the late 30s and early 40s then gradually declines thereafter, although not to the same low levels that characterized early adulthood. Peak times of creative achievement also vary from field to field. The productivity of scholars in the humanities (for example, that of philosophers or historians) continues well into old age and peaks in the 60s, possibly because creative work in these fields often involves integrating knowledge that has crystallized over the years. By contrast, productivity in the arts (for example, music or drama) peaks in the 30s and 40s and declines steeply thereafter, because artistic creativity depends on a more fluid or innovative kind of thinking. Scientists seem to be intermediate, peaking in their 40s and declining only in their 70s. Even with the same general field, differences in peak times have been noted. For example, poets reach their peak before novelists do, and mathematicians peak before other scientists do.

Greer is more interested in creativity than raw cognition — his essay linked above is pondering why public intellectuals seem to have short shelf-lives. So it makes sense when thinking about careers whose output involves synthesis of crystallized knowledge that a peak in early middle life is to be expected, after accumulating lots of experience but before general cognitive decline becomes too advanced to seriously impede one’s facility with analyzing and manipulating that knowledge.

But what about us non-scholars, those of us in the general knowledge economy, we whose economic viability depends on rapidly learning new skills and tools on demand in a constantly shifting landscape? Mark Zuckerberg ruffled feathers when he publicly stated his preference for younger employees, saying “young people are just smarter” than their older peers. But he was right. It might be illegal to discriminate against older people in hiring, but it’s objectively correct to expect them to be slower to learn and grow on the job. We may bring more to the table in terms of our experience, but it’s simple vanity to insist we can keep up with the fresh-faced kids. And when your experience counts for little because the entire industry’s tech stack rotates every five years, then what?

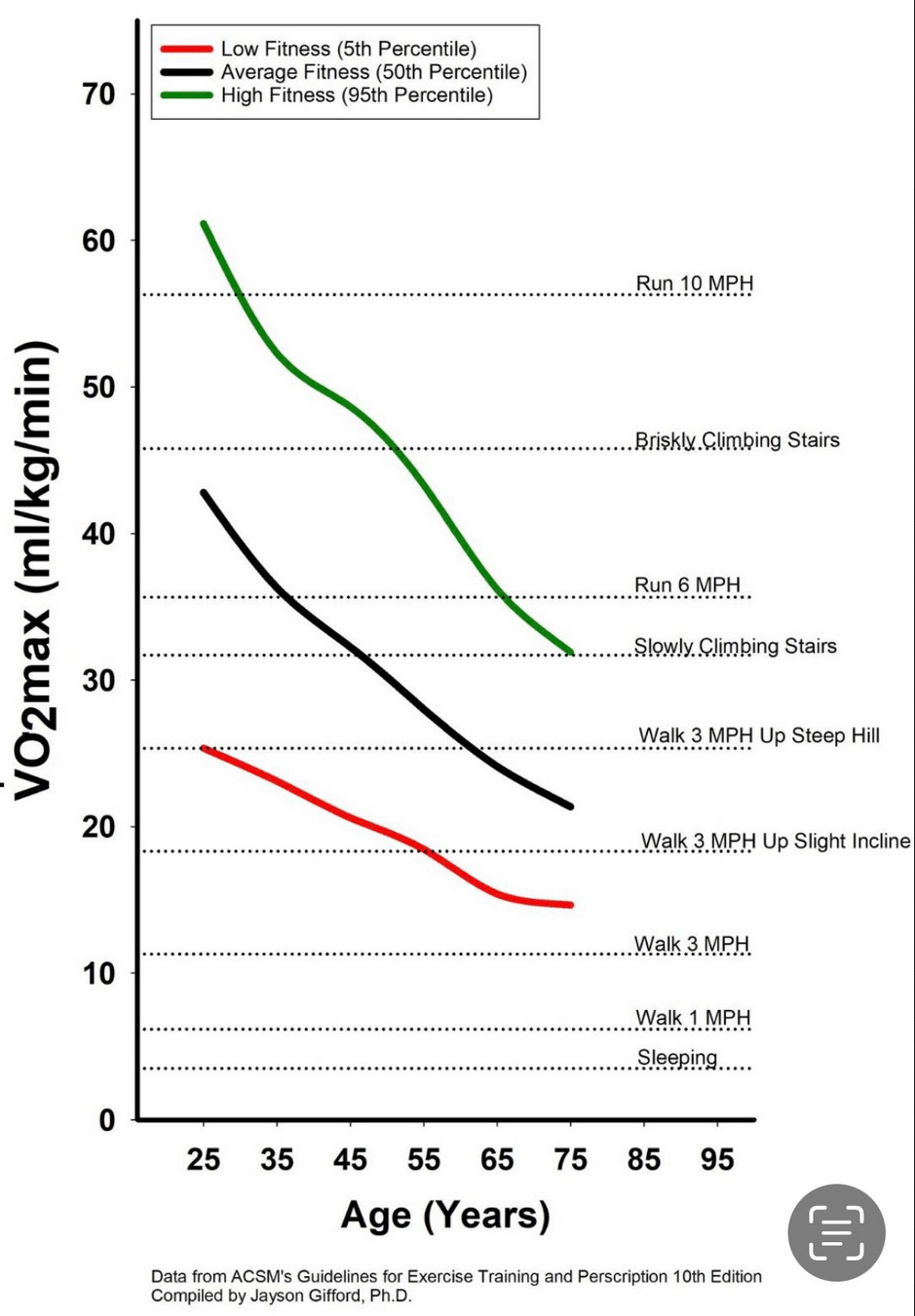

Forgive me for only discussing these nerdy brain concerns. I don’t want to give my loyal readers the impression that I’m one of those un-embodied weaklings, out of touch with the beauty of his own strength and physical prowess. In fact I take nearly as great a pride in my grace and endurance, in the capabilities of my physical body, as I do in my meaty intellect. But here again I can find no relief from the ravages of time. In the physical realm the situation is if anything even more dire than in the realm of the mind. At age 25, a 95th percentile performance among men means you can run under a 6-minute mile. At age 75, a 95th percentile performance means you can slowly climb stairs.

This is a shocking level of decline, but if anything it undersells the true horror of aging. Everyone understands that loss of physical performance is part of getting older, even if they’ve never quite internalized how steep that loss will be. But radically reduced VO2 max is just the tip of the iceberg.

Even by my thirties I noticed my body taking much longer to recover from injuries, and eventually came to the grim realization that new wounds would never fully, 100% heal. From that point on, I was playing for keeps: each sprain or torn muscle would be with me for the rest of my life, no question. Now in my forties, the injuries I sustained as a younger man continually return to haunt me, aches and pains from accidents decades ago. Sometimes I’ll be in pain all day because of how I slept the night before. And under it all: inexorable metabolic decline, decreased organ function, slowly accumulating, irreparable cellular damage.

I haven’t mentioned concerns about appearance, but that’s only because I’m not a woman. Women’s anxiety around aging drives 20% of consumer spending, conservatively.

I’m sorry to be a downer. Aging sucks, and anyone telling you differently is trying to sell you something. The only positive aspect is getting to finally reap the benefits of a life well lived, assuming you lived well: the love of family, a nice place to live, financial security, a firmer grasp of the world and your place in it. I’m very blessed to have all of these. I know many aren’t so lucky.

And one more positive aspect: learning to let go of youthful anxiety about legacy. Like many precocious and sensitive young men, preoccupation with this topic sometimes weighed heavily on me in my youth. Surely I would accomplish the great things my teachers and peers always assured me I would, surely my achievements would echo down through the ages. But as I crested my late twenties and entered my thirties, I began to worry: when? Simply earning a lot of money, some promotions and other career accolades, a collection of hobbies and skills, minor notoriety online, the odd bullshit patent or publication, surely those things didn’t qualify as true greatness. And no, they didn’t, they don’t. This used to gnaw at me, and it doesn’t anymore. Now in the twilight of my youth, on the threshold of true middle age, the only legacy I care about is biological and material, the success of my children and their children, what I’ll provide them and how they’ll remember me. I expect many men begin to feel the same way as they approach my age.

Or maybe they don’t. Maybe they’re consumed by the fear that they’re working against the clock and will ultimately lose the race with their own inevitable decline before leaving a mark that satisfies them. Probably many of them are right. I understand completely. Just because I’ve made peace with my lack of greatness doesn’t mean I like it.

I write these essays because I’m compelled to, for reasons that remain partly mysterious to me, but that must surely involve some large dose of ego, with leaving a record that persists beyond my frail mortal shell. The idea of my great-grandchildren and their peers reading my shitposts in snatches of intermittent electrical coverage in between dodging the seeker-killer robots hunting them in the ruins of industrial civilization, of finding some joy or insight therein, does make me smile. It makes me feel like I really will outlive myself, the same way those great-grandchildren will outlive me, and carry part of me with them. And isn’t that what we all hope for, when we think about getting old and dying? That it will all have meant something. That the things we did in life, what we leave to those who come after us, will in some small way make a difference. That we mattered, and lasted beyond ourselves.

At 72 years old, I am more fit than I was at 30, and just as sharp cognitively. Of course, when I was 30, I was a slovenly layabout living on coffee cake.

So I’m 40, and what strikes me about aging is just the degree of discipline I’ve developed over the years/decades. This always seems to be a forgotten advantage of getting older: the increasing level of self-control. Learning a new skill might be harder, but picking up a new habit is easier. This is coupled with more regulated moods and accumulated wisdom in planning one’s activity and thinking.

Having kids puts that virtue to the test. As a father, your job is to impose that discipline and self-control over a people teeming with energy and turbulence. If you’re too young, you’ll likely crack and run away. But with this honed fortitude pushing back against the chaos, you can get that yin-yang balance of healthy family life.