Stochastic martyrdom

The soccer mom's veto

One of the most remarkable and disturbing aspects of the ICE confrontation videos coming out is the prevalence of women physically engaging law enforcement, especially given their clear belief that they will not come to harm by obstructing and outright attacking heavily armed state agents. Renee Good lost her life in such a confrontation, and footage from four different angles documented the chillingly playful manner in which she and her wife taunted the ICE officers whose vehicle they were blocking. Right up until the moment of her fatal shooting, Good clearly believed herself to be completely untouchable by federal agents armed with deadly weapons. To look at her face mere seconds from death is to see a woman engaged in playfighting, someone incapable of imagining that stalking men with guns, blocking their vehicles, ignoring their orders to desist, to leave her car, could possibly get her hurt. Whatever you think of the legality of Good’s shooting, the fact that she seemed to sleepwalk into it, blithely oblivious to the extreme peril in which she placed herself, should disturb you. It disturbs me.

But the truly disturbing part is that Good’s behavior is far from an outlier. German blogger eugyppius recently echoed my own shock at how quickly activist tactics have escalated in his essay Courting death to own the Nazis. In the excerpt below he’s describing not Renee Good’s fatal encounter with immigration police, but another white woman in Minnesota successfully employing the exact same tactic Good used, blocking a public road to prevent an ICE vehicle from moving, and proudly posting the entire episode to TikTok. You don’t know her name because she survived the incident she incited without injury, but she’s one of thousands of newly radicalized activists playing a dangerous game of interference with federal law enforcement. Click through to watch the video, it’s very illustrative.

The most instructive moment in this clip (again, one of dozens) comes right at the beginning, when our heroine tells the ICE agents whose car she is blocking that “We can play” because “my car’s bigger than yours.” This random woman who probably has kids in school and a mortgage and a miserable ex-husband on the hook for god knows how much in child support thus openly contemplates weaponising her vehicle against multiple armed law enforcement officers. That level of middle-class political radicalisation is pretty amazing if you ask me.

Objectively speaking, these ICE-watching women engage federal law enforcement officers in repeated rounds of chicken. Their aim is to edge beyond being a mere nuisance and cause meaningful disruptions, while hoping always to stop short of becoming a serious, actionable threat. This is a very hard balance to maintain because of course threats are perceived subjectively. Where exactly the line falls will vary from officer to officer and from situation to situation, according to a multitude of imponderables. Anyone who plays like this is trying to get shot, whether she realises it or not.

“We can play,” the soccer mom monologues to TikTok while maneuvering her car to prevent an SUV of heavily armed men from driving down a public street. Like Good, the fact that her actions are incredibly dangerous, that her situation could unpredictably spiral out of control and result in her death or someone else’s, seems to never cross her mind. Why are so many middle-class people, and especially women, behaving with such reckless disregard for their own safety, seemingly without realizing it? Yes, they oppose immigration enforcement, they consider ICE’s mission illegitimate. But most people who hold these views do not engage in direct action with armed law enforcement, and even fewer would put themselves in a position to be beaten or shot by physically obstructing or interfering with officers. Yet a critical minority of mostly white, mostly middle-class activists, disproportionately women, have been radicalized into this extreme form of activist protest in large numbers. How did this happen?

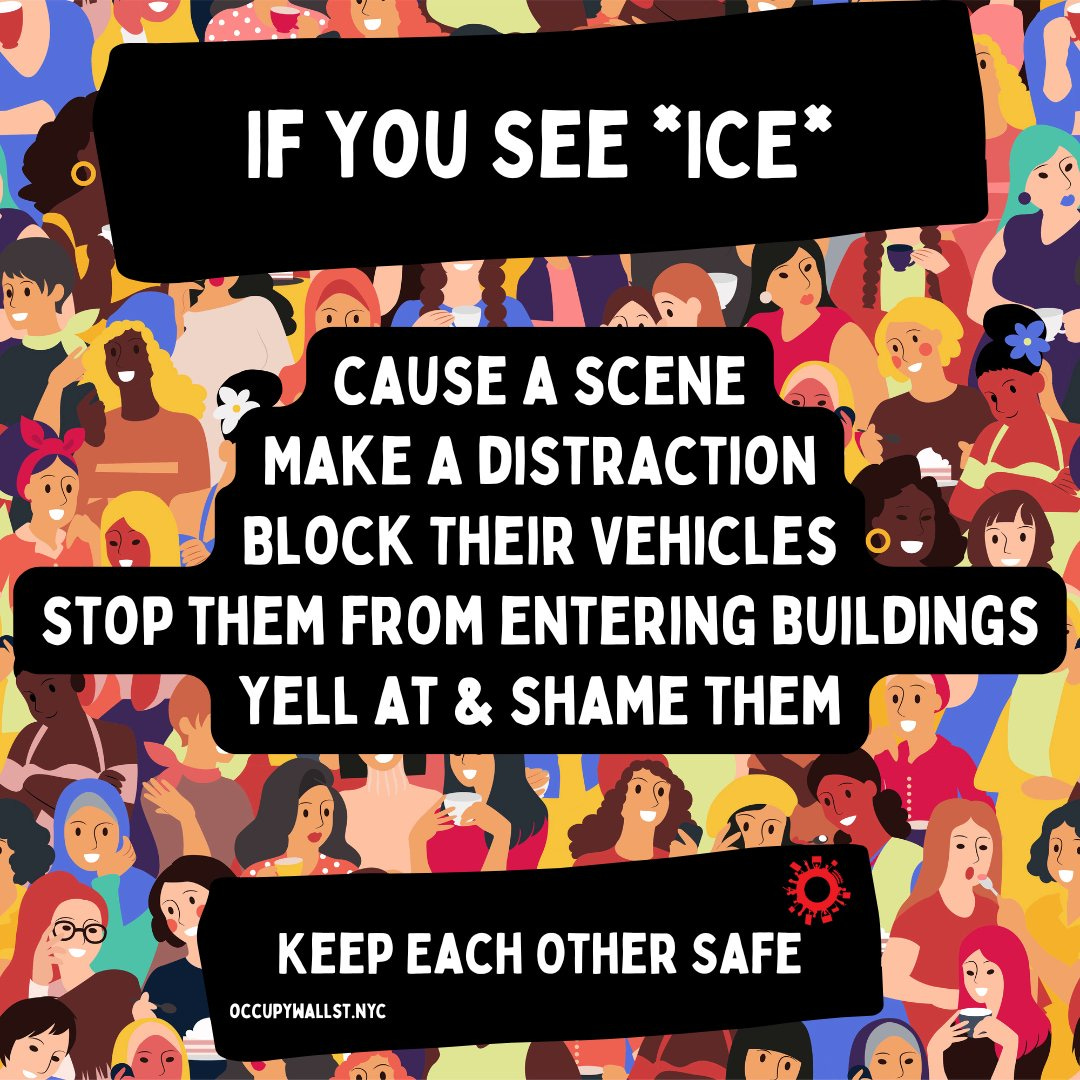

To understand why, first understand that activist groups of the kind that Good belonged to encourage their members to use the exact interference tactics she employed, as well as other, even more dangerous ones. These groups publish various guides on how to prevent law enforcement from fulfilling their mission or arresting their fellow travelers. They conduct training sessions for members to rehearse these tactics before deploying them in the field. They are well organized and well funded.

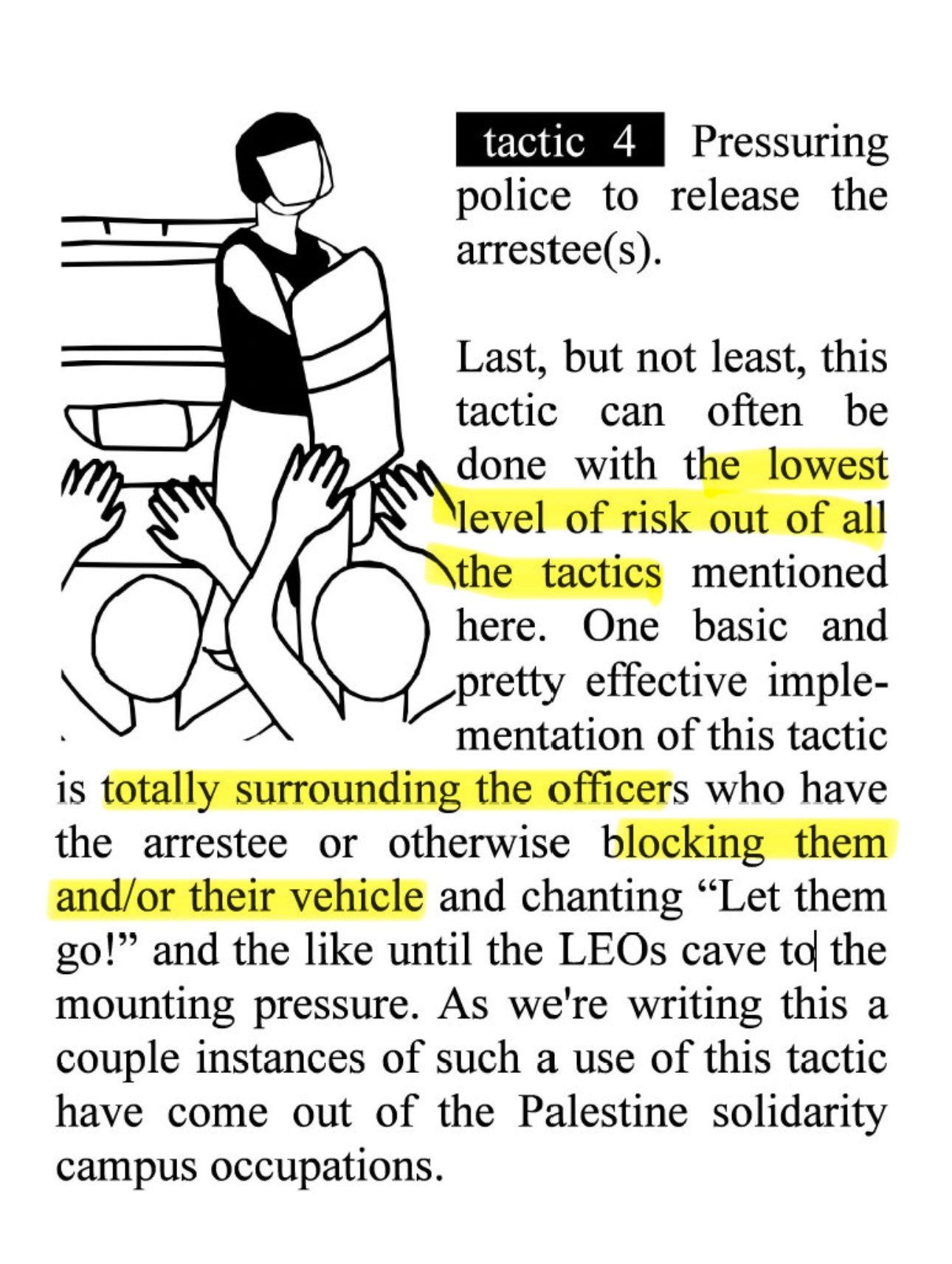

Below is an excerpt from a publication circulated by ICE Watch Minnesota, one of the activist groups with which Good was reportedly affiliated. Here they advocate surrounding law enforcement officers with civilian cars as a “de-arrest” strategy, calling this tactic “the lowest level of risk”.

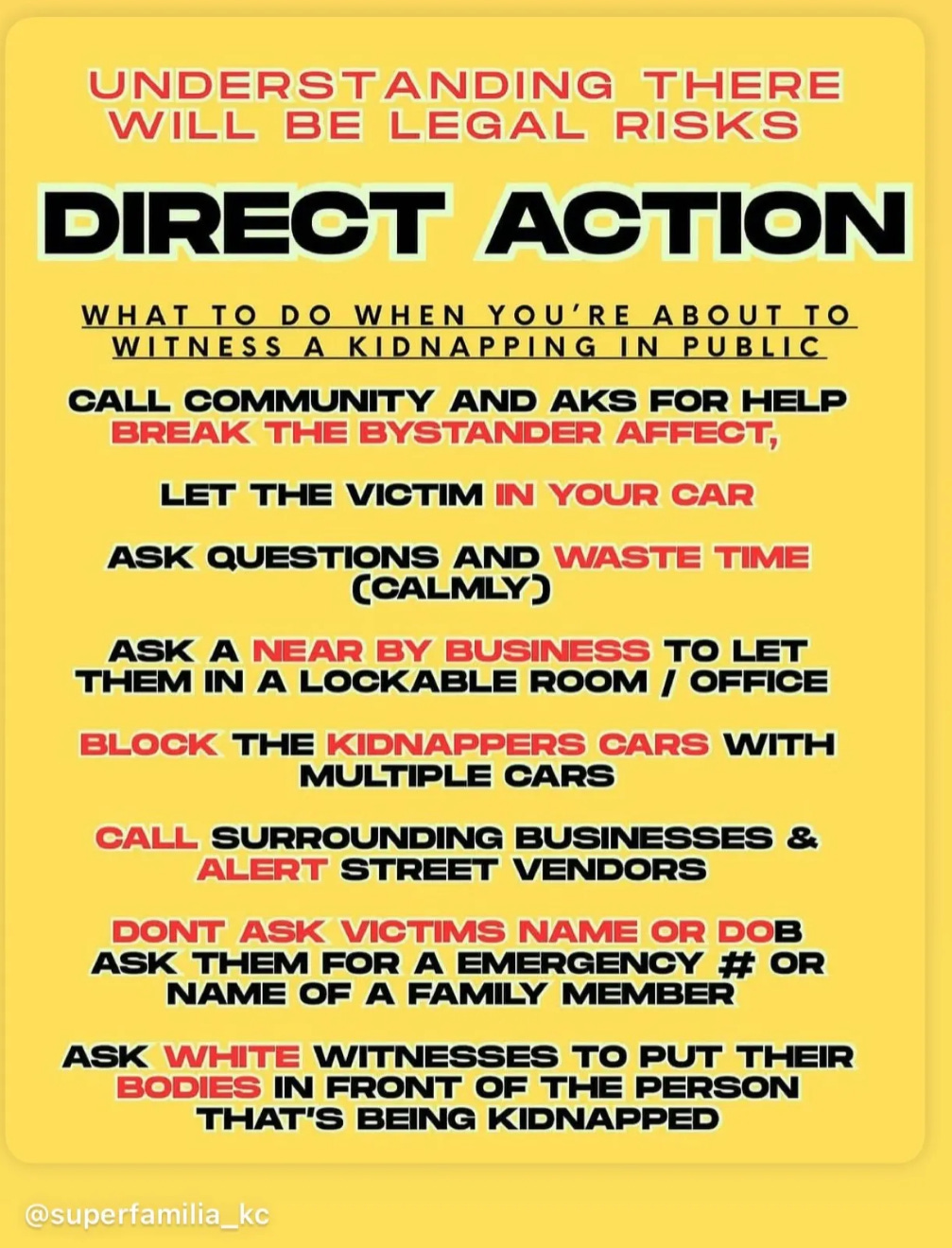

The group also shared the following flyer on Instagram, encouraging its membership to interfere with ICE operations by “block[ing] the kidnappers cars with multiple cars” and “ask[ing] white witnesses to put their bodies” in the way of officers. If this advice sounds familiar, it should.

The citizen-led anti-ICE operations taking place in Minneapolis and in every city where ICE shows its masked faces are better understood as a kind of militia action, rather than as a form of protest. Even when technically non-violent in nature, these operations are designed to provoke a violent response from law enforcement, thereby producing mediagenic victims to use in propaganda. The goal is to trap enforcement efforts in a double bind — either obstruction tactics disrupt immigration enforcement, so activists win; or somebody gets hurt or killed for the dozens of cameras filming every encounter, producing a new martyr to dominate media coverage, so activists win.

Activist networks encourage their members to engage in behavior that they know will result in martyr production when applied at scale in a simple equation: X activists engaging with Y officers per day with a violent confrontation rate of Z% will lead to N new martyrs per year. The logic is as predictable as it is sad. Each new martyrdom is not a regrettable tragedy, it is a tremendous boon to the movement, motivating swells of protest and inducing fresh blood to enlist so the cycle can continue.

A few months ago I tried to organize my thoughts about whether we are at war in light of the increasing frequency of this kind of conflict, and discussed the role of so-called “stochastic terrorism”, the idea that broadcasting an urgent moral crisis will predictably lead some number of your least stable listeners to take violent action.

Everyone understands, at a gut level, that the language of existential conflict, spoken by serious national figures and broadcast widely, is a call to violence that someone, somewhere, will take literally and act on. The official term for this in 2025 is stochastic terrorism, and the danger of such terrorism from the right was breathlessly discussed as a major concern by the left in a series of hand-wringing interviews and media puff pieces right up until the moment that two separate assassins made attempts on Trump’s life. Since then the term has been quietly mothballed, because to take it seriously implicates Joy Reid and MSNBC, to say nothing of many sitting Senators, in our ongoing political violence. If you tell your supporters that democracy and our way of life are at stake, that a literal fascist dictator is coming into power, and you repeat these messages non-stop for the better part of a decade, you cannot then act surprised when somebody takes a shot at Orange Hitler.

Stochastic terrorism is a vital concept in understanding the fourth-generation warfare of our slowly simmering maybe-civil-war, and I’d like to submit a related term for consideration: stochastic martyrdom1.

Stochastic martyrdom is the encouragement of activist tactics that will predictably get activists hurt or killed when applied at scale, coupled with false assurances of personal safety for the people employing them. The martyrs created by this process are then used (quite effectively) as propaganda for the activist cause in a positive feedback loop. The repeated assurances that radically dangerous tactics are actually perfectly safe explains the preponderance of women throwing themselves in harm’s way, as well as the uncanny “we’re just playing” affect adopted by so many of the women filming themselves confronting officers armed with lethal weapons. And the importance of these false assurances explain the widely circulating myths that federal immigration officers can’t touch or arrest US citizens, that they have no authority over you to order you to (for example) stop blocking a public road, like a sort of leftist sovereign citizen movement. Obviously these ideas are dangerous lies, and I would bet money that Good had heard and believed them.

I ended that essay a few months ago by concluding that, no, we probably aren’t at war. Not by most recognizable definitions, not by historical comparisons with conditions we did not call war at the time and don’t today.

And if this is a war, it’s a pretty genteel one at the moment. Recalling Days of Rage again:

“People have completely forgotten that in 1972 we had over nineteen hundred domestic bombings in the United States.” — Max Noel, FBI (ret.)

I still think that’s true. There’s a certain sense in which the escalating political violence we’re experiencing is a cold civil war, and it can be useful to think of it that way in certain contexts. But for the most part, for most daily uses, I would call that label a distraction. To me, the more salient issue is the breakdown of consensus around the legitimacy of law and law enforcement in general. In the case of immigration law in particular, a very sizable minority of our fellow citizens do not consider ICE or its mission legitimate, an attitude which echoes broadly voiced doubts about the legitimacy of policing as a whole during the Summer of Floyd. And there’s an obvious parallel to the capitol riots on January 6, when partisans attempted to interfere with the lawful execution of a federal election on the grounds that various alleged dirty tricks and irregularities made its result illegitimate. That resulted in an activist death too, although one that got significantly less sympathetic press coverage. In both examples, we saw sizable groups willing to confront with direct action what they perceived as illegitimate laws, and in both cases participants possessed an uncanny and false belief in their own safety in pursuing such action. These conditions are guaranteed to produce a steady stream of violence and martyrs.

The battle over ICE is nowhere near settled, it’s certainly not the last source of political violence we’ll see during this administration or the next, and my guess is that things are going to get worse before they get better. I remain hopeful that the forgotten and nearly unbelievable level of violence of the early 1970s will not come to pass again. But I wouldn’t count on it.

Several of my followers on Twitter suggested this term in replies to various tweets of mine on this topic, and I’m shamelessly stealing it to propagate here.

For a long time I've noticed (as many have) the disconnect between the seriousness of people's rhetoric (expressed desire for violence etc) and the non-seriousness/flippancy/casualness with which it is expressed (calling for assassinations at the work brunch or whatever.

This seems like a similar phenomenon, but extended from rhetoric to action---still treated like a tribe signaling game. They dont expect to face violent consequences for the same reason they dont expect you to press them on their views at the work brunch.

Three thing to add: 1) this isn't new, their mothers/grandmothers were putting flower in the barrels of National Guard rifles in the 60s (another reminder that current levels of unrest are a shadow of what used to be) 2) this isn't limited to the left - would it surprise anyone that read this that the only person shot by law enforcement on Jan 6 was a *drumroll* white woman? 3) this is certainly better than the alternative, which is Americans cowering in fear of a vast internal police force.